- Home

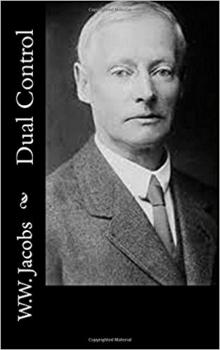

- W. W. Jacobs

Husbandry

Husbandry Read online

Produced by David Widger

DEEP WATERS

By W.W. JACOBS

HUSBANDRY

Dealing with a man, said the night-watchman, thoughtfully, is as easy asa teetotaller walking along a nice wide pavement; dealing with a woman islike the same teetotaller, arter four or five whiskies, trying to get upa step that ain't there. If a man can't get 'is own way he eases 'ismind with a little nasty language, and then forgets all about it; if awoman can't get 'er own way she flies into a temper and reminds you ofsomething you oughtn't to ha' done ten years ago. Wot a woman would dowhose 'usband had never done anything wrong I can't think.

I remember a young feller telling me about a row he 'ad with 'is wifeonce. He 'adn't been married long and he talked as if the way shecarried on was unusual. Fust of all, he said, she spoke to 'im in acooing sort o' voice and pulled his moustache, then when he wouldn't giveway she worked herself up into a temper and said things about 'is sister.Arter which she went out o' the room and banged the door so hard it blewdown a vase off the fireplace. Four times she came back to tell 'imother things she 'ad thought of, and then she got so upset she 'ad to goup to bed and lay down instead of getting his tea. When that didn't dono good she refused her food, and when 'e took her up toast and tea shewouldn't look at it. Said she wanted to die. He got quite uneasy till'e came 'ome the next night and found the best part of a loaf o' bread, aquarter o' butter, and a couple o' chops he 'ad got in for 'is supper hadgorn; and then when he said 'e was glad she 'ad got 'er appetite back sheturned round and said that he grudged 'er the food she ate.

And no woman ever owned up as 'ow she was wrong; and the more you try andprove it to 'em the louder they talk about something else. I know wotI'm talking about because a woman made a mistake about me once, andthough she was proved to be in the wrong, and it was years ago, my missusshakes her 'ead about it to this day.

It was about eight years arter I 'ad left off going to sea and took upnight-watching. A beautiful summer evening it was, and I was sitting bythe gate smoking a pipe till it should be time to light up, when Inoticed a woman who 'ad just passed turn back and stand staring at me.I've 'ad that sort o' thing before, and I went on smoking and lookingstraight in front of me. Fat middle-aged woman she was, wot 'ad lost hergood looks and found others. She stood there staring and staring, and byand by she tries a little cough.

I got up very slow then, and, arter looking all round at the evening,without seeing 'er, I was just going to step inside and shut the wicket,when she came closer.

"Bill!" she ses, in a choking sort o' voice.

"Bill!"

I gave her a look that made her catch 'er breath, and I was just steppingthrough the wicket, when she laid hold of my coat and tried to hold meback.

"Do you know wot you're a-doing of?" I ses, turning on her.

"Oh, Bill dear," she ses, "don't talk to me like that. Do you want tobreak my 'art? Arter all these years!"

She pulled out a dirt-coloured pocket-'ankercher and stood there dabbingher eyes with it. One eye at a time she dabbed, while she looked at mereproachful with the other. And arter eight dabs, four to each eye, shebegan to sob as if her 'art would break.

"Go away," I ses, very slow. "You can't stand making that noise outsidemy wharf. Go away and give somebody else a treat."

Afore she could say anything the potman from the Tiger, a nasty ginger-'aired little chap that nobody liked, come by and stopped to pat her onthe back.

"There, there, don't take on, mother," he ses. "Wot's he been a-doing toyou?"

"You get off 'ome," I ses, losing my temper.

"Wot d'ye mean trying to drag me into it? I've never seen the womanafore in my life."

"Oh, Bill!" ses the woman, sobbing louder than ever. "Oh! Oh! Oh!"

"'Ow does she know your name, then?" ses the little beast of a potman.

I didn't answer him. I might have told 'im that there's about fivemillion Bills in England, but I didn't. I stood there with my armsfolded acrost my chest, and looked at him, superior.

"Where 'ave you been all this long, long time?" she ses, between hersobs. "Why did you leave your happy 'ome and your children wot lovedyou?"

The potman let off a whistle that you could have 'eard acrost the river,and as for me, I thought I should ha' dropped. To have a woman standingsobbing and taking my character away like that was a'most more than Icould bear.

"Did he run away from you?" ses the potman.

"Ye-ye-yes," she ses. "He went off on a vy'ge to China over nine yearsago, and that's the last I saw of 'im till to-night. A lady friend o'mine thought she reckernized 'im yesterday, and told me."

"I shouldn't cry over 'im," ses the potman, shaking his 'ead: "he ain'tworth it. If I was you I should just give 'im a bang or two over the'ead with my umberella, and then give 'im in charge."

I stepped inside the wicket--backwards--and then I slammed it in theirfaces, and putting the key in my pocket, walked up the wharf. I knew itwas no good standing out there argufying. I felt sorry for the porething in a way. If she really thought I was her 'usband, and she 'adlost me---- I put one or two things straight and then, for the sake ofdistracting my mind, I 'ad a word or two with the skipper of the JohnHenry, who was leaning against the side of his ship, smoking.

"Wot's that tapping noise?" he ses, all of a sudden. "'Ark!"

I knew wot it was. It was the handle of that umberella 'ammering on thegate. I went cold all over, and then when I thought that the pot-man wasmost likely encouraging 'er to do it I began to boil.

"Somebody at the gate," ses the skipper.

"Aye, aye," I ses. "I know all about it."

I went on talking until at last the skipper asked me whether he waswandering in 'is mind, or whether I was. The mate came up from the cabinjust then, and o' course he 'ad to tell me there was somebody knocking atthe gate.

"Ain't you going to open it?" ses the skipper, staring at me.

"Let 'em ring," I ses, off-hand.

The words was 'ardly out of my mouth afore they did ring, and if they 'adbeen selling muffins they couldn't ha' kept it up harder. And all thetime the umberella was doing rat-a-tat tats on the gate, while a voice--much too loud for the potman's--started calling out: "Watch-man ahoy!"

"They're calling you, Bill," ses the skipper. "I ain't deaf," I ses,very cold.

"Well, I wish I was," ses the skipper. "It's fair making my ear ache.Why the blazes don't you do your dooty, and open the gate?"

"You mind your bisness and I'll mind mine," I ses. "I know wot I'mdoing. It's just some silly fools 'aving a game with me, and I'm notgoing to encourage 'em."

"Game with you?" ses the skipper. "Ain't they got anything better thanthat to play with? Look 'ere, if you don't open that gate, I will."

"It's nothing to do with you," I ses. "You look arter your ship and I'lllook arter my wharf. See? If you don't like the noise, go down in thecabin and stick your 'ead in a biscuit-bag."

To my surprise he took the mate by the arm and went, and I was justthinking wot a good thing it was to be a bit firm with people sometimes,when they came back dressed up in their coats and bowler-hats and climbedon to the wharf.

"Watchman!" ses the skipper, in a hoity-toity sort o' voice, "me and themate is going as far as Aldgate for a breath o' fresh air. Open thegate."

I gave him a look that might ha' melted a 'art of stone, and all it doneto 'im was to make 'im laugh.

"Hurry up," he ses. "It a'most seems to me that there's somebody ringingthe bell, and you can let them in same time as you let us out. Is it thebell, or is it my fancy, Joe?" he ses, turning to the mate.

They marched on in front of me with their noses cocked in the air, andall the time the noise at the gate got worse and wors

e. So far as Icould make out, there was quite a crowd outside, and I stood there withthe key in the lock, trembling all over. Then I unlocked it verycareful, and put my hand on the skipper's arm.

"Nip out quick," I ses, in a

_preview.jpg) Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection)

Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection) The Monkey's Paw

The Monkey's Paw Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II

Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II Odd Craft, Complete

Odd Craft, Complete The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection

The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection Deep Waters, the Entire Collection

Deep Waters, the Entire Collection Three at Table

Three at Table Light Freights

Light Freights Night Watches

Night Watches The Three Sisters

The Three Sisters Ship's Company, the Entire Collection

Ship's Company, the Entire Collection His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts

His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts Fine Feathers

Fine Feathers My Man Sandy

My Man Sandy Self-Help

Self-Help Captains All and Others

Captains All and Others Back to Back

Back to Back More Cargoes

More Cargoes Believe You Me!

Believe You Me! Keeping Up Appearances

Keeping Up Appearances The Statesmen Snowbound

The Statesmen Snowbound An Adulteration Act

An Adulteration Act The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches

The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches Husbandry

Husbandry Love and the Ironmonger

Love and the Ironmonger The Old Man's Bag

The Old Man's Bag Dirty Work

Dirty Work Easy Money

Easy Money The Lady of the Barge

The Lady of the Barge Bedridden and the Winter Offensive

Bedridden and the Winter Offensive Odd Charges

Odd Charges Friends in Need

Friends in Need Watch-Dogs

Watch-Dogs Cupboard Love

Cupboard Love Captains All

Captains All A Spirit of Avarice

A Spirit of Avarice The Nest Egg

The Nest Egg The Guardian Angel

The Guardian Angel The Convert

The Convert Captain Rogers

Captain Rogers Breaking a Spell

Breaking a Spell Striking Hard

Striking Hard The Bequest

The Bequest Shareholders

Shareholders The Weaker Vessel

The Weaker Vessel John Henry Smith

John Henry Smith Four Pigeons

Four Pigeons Made to Measure

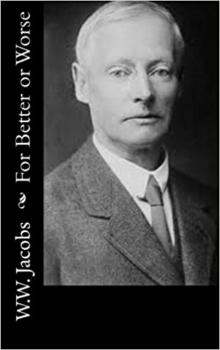

Made to Measure For Better or Worse

For Better or Worse Fairy Gold

Fairy Gold Family Cares

Family Cares Good Intentions

Good Intentions Prize Money

Prize Money The Temptation of Samuel Burge

The Temptation of Samuel Burge The Madness of Mr. Lister

The Madness of Mr. Lister The Constable's Move

The Constable's Move Paying Off

Paying Off Double Dealing

Double Dealing A Mixed Proposal

A Mixed Proposal Bill's Paper Chase

Bill's Paper Chase The Changing Numbers

The Changing Numbers Over the Side

Over the Side Lawyer Quince

Lawyer Quince The White Cat

The White Cat Admiral Peters

Admiral Peters The Third String

The Third String The Vigil

The Vigil Bill's Lapse

Bill's Lapse His Other Self

His Other Self Matrimonial Openings

Matrimonial Openings The Substitute

The Substitute Deserted

Deserted Dual Control

Dual Control Homeward Bound

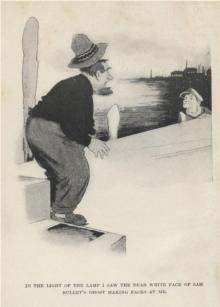

Homeward Bound Sam's Ghost

Sam's Ghost The Unknown

The Unknown Stepping Backwards

Stepping Backwards Sentence Deferred

Sentence Deferred The Persecution of Bob Pretty

The Persecution of Bob Pretty Skilled Assistance

Skilled Assistance A Golden Venture

A Golden Venture Establishing Relations

Establishing Relations A Tiger's Skin

A Tiger's Skin Bob's Redemption

Bob's Redemption Manners Makyth Man

Manners Makyth Man The Head of the Family

The Head of the Family The Understudy

The Understudy Odd Man Out

Odd Man Out Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary

Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence Blundell's Improvement

Blundell's Improvement The Toll-House

The Toll-House Dixon's Return

Dixon's Return Keeping Watch

Keeping Watch The Boatswain's Mate

The Boatswain's Mate The Castaway

The Castaway In the Library

In the Library The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre