- Home

- W. W. Jacobs

Dirty Work

Dirty Work Read online

Produced by David Widger

DEEP WATERS

By W.W. JACOBS

DIRTY WORK

It was nearly high-water, and the night-watchman, who had stepped aboarda lighter lying alongside the wharf to smoke a pipe, sat with half-closedeyes enjoying the summer evening. The bustle of the day was over, thewharves were deserted, and hardly a craft moved on the river. Perfumedclouds of shag, hovering for a time over the lighter, floated lazilytowards the Surrey shore.

"There's one thing about my job," said the night-watchman, slowly, "it'sdone all alone by yourself. There's no foreman a-hollering at you andoffering you a penny for your thoughts, and no mates to run into you frombehind with a loaded truck and then ask you why you didn't look whereyou're going to. From six o'clock in the evening to six o'clock nextmorning I'm my own master."

He rammed down the tobacco with an experienced forefinger and puffedcontentedly.

People like you 'ud find it lonely (he continued, after a pause); I didat fust. I used to let people come and sit 'ere with me of an eveningtalking, but I got tired of it arter a time, and when one chap felloverboard while 'e was showing me 'ow he put his wife's mother in 'erplace, I gave it up altogether. There was three foot o' mud in the dockat the time, and arter I 'ad got 'im out, he fainted in my arms.

Arter that I kept myself to myself. Say wot you like, a man's bestfriend is 'imself. There's nobody else'll do as much for 'im, or let 'imoff easier when he makes a mistake. If I felt a bit lonely I used toopen the wicket in the gate and sit there watching the road, and p'r'apspass a word or two with the policeman. Then something 'appened one nightthat made me take quite a dislike to it for a time.

I was sitting there with my feet outside, smoking a quiet pipe, when I'eard a bit of a noise in the distance. Then I 'eard people running andshouts of "Stop, thief!" A man came along round the corner full pelt,and, just as I got up, dashed through the wicket and ran on to the wharf.I was arter 'im like a shot and got up to 'im just in time to see himthrow something into the dock. And at the same moment I 'eard the otherpeople run past the gate.

"Wot's up?" I ses, collaring 'im.

"Nothing," he ses, breathing 'ard and struggling. "Let me go."

He was a little wisp of a man, and I shook 'im like a dog shakes a rat.I remembered my own pocket being picked, and I nearly shook the breathout of 'im.

"And now I'm going to give you in charge," I ses, pushing 'im alongtowards the gate.

"Wot for?" he ses, purtending to be surprised.

"Stealing," I ses.

"You've made a mistake," he ses; "you can search me if you like."

"More use to search the dock," I ses. "I see you throw it in. Now youkeep quiet, else you'll get 'urt. If you get five years I shall be allthe more pleased."

I don't know 'ow he did it, but 'e did. He seemed to sink away betweenmy legs, and afore I knew wot was 'appening, I was standing upside downwith all the blood rushing to my 'ead. As I rolled over he boltedthrough the wicket, and was off like a flash of lightning.

A couple o' minutes arterwards the people wot I 'ad 'eard run past cameback agin. There was a big fat policeman with 'em--a man I'd seen aforeon the beat--and, when they 'ad gorn on, he stopped to 'ave a word withme.

"'Ot work," he ses, taking off his 'elmet and wiping his bald 'ead with alarge red handkerchief. "I've lost all my puff."

"Been running?" I ses, very perlite.

"Arter a pickpocket," he ses. "He snatched a lady's purse just as shewas stepping aboard the French boat with her 'usband. 'Twelve pounds init in gold, two peppermint lozenges, and a postage stamp.'"

He shook his 'ead, and put his 'elmet on agin.

"Holding it in her little 'and as usual," he ses. "Asking for trouble, Icall it. I believe if a woman 'ad one hand off and only a finger andthumb left on the other, she'd carry 'er purse in it."

He knew a'most as much about wimmen as I do. When 'is fust wife died,she said 'er only wish was that she could take 'im with her, and she made'im promise her faithful that 'e'd never marry agin. His second wife,arter a long illness, passed away while he was playing hymns on theconcertina to her, and 'er mother, arter looking at 'er very hard, wentto the doctor and said she wanted an inquest.

He went on talking for a long time, but I was busy doing a bit of 'ead-work and didn't pay much attention to 'im. I was thinking o' twelvepounds, two lozenges, and a postage stamp laying in the mud at the bottomof my dock, and arter a time 'e said 'e see as 'ow I was waiting to getback to my night's rest, and went off--stamping.

I locked the wicket when he 'ad gorn away, and then I went to the edge ofthe dock and stood looking down at the spot where the purse 'ad beenchucked in. The tide was on the ebb, but there was still a foot or twoof water atop of the mud. I walked up and down, thinking.

I thought for a long time, and then I made up my mind. If I got thepurse and took it to the police-station, the police would share the moneyout between 'em, and tell me they 'ad given it back to the lady. If Ifound it and put a notice in the newspaper--which would cost money--verylikely a dozen or two ladies would come and see me and say it was theirs.Then if I gave it to the best-looking one and the one it belonged toturned up, there'd be trouble. My idea was to keep it--for a time--andthen if the lady who lost it came to me and asked me for it I would giveit to 'er.

Once I had made up my mind to do wot was right I felt quite 'appy, andarter a look up and down, I stepped round to the Bear's Head and 'ad acouple o' goes o' rum to keep the cold out. There was nobody in therebut the landlord, and 'e started at once talking about the thief, and 'owhe 'ad run arter him in 'is shirt-sleeves.

"My opinion is," he ses, "that 'e bolted on one of the wharves and 'id'imself. He disappeared like magic. Was that little gate o' yoursopen?"

"I was on the wharf," I ses, very cold.

"You might ha' been on the wharf and yet not 'ave seen anybody come on,"he ses, nodding.

"Wot d'ye mean?" I ses, very sharp. "Nothing," he ses. "Nothing."

"Are you trying to take my character away?" I ses, fixing 'im with myeye.

"Lo' bless me, no!" he ses, staring at me. "It's no good to me."

He sat down in 'is chair behind the bar and went straight off to sleepwith his eyes screwed up as tight as they would go. Then 'e openedhis mouth and snored till the glasses shook. I suppose I've been one ofthe best customers he ever 'ad, and that's the way he treated me. Fortwo pins I'd ha' knocked 'is ugly 'ead off, but arter waking him up verysudden by dropping my glass on the floor I went off back to the wharf.

I locked up agin, and 'ad another look at the dock. The water 'ad nearlygone and the mud was showing in patches. My mind went back to asailorman wot had dropped 'is watch over-board two years before, andfound it by walking about in the dock in 'is bare feet. He found it moreeasy because the glass broke when he trod on it.

The evening was a trifle chilly for June, but I've been used to roughingit all my life, especially when I was afloat, and I went into the officeand began to take my clothes off. I took off everything but my pants,and I made sure o' them by making braces for 'em out of a bit of string.Then I turned the gas low, and, arter slipping on my boots, went outside.

It was so cold that at fust I thought I'd give up the idea. The longer Istood on the edge looking at the mud the colder it looked, but at last Iturned round and went slowly down the ladder. I waited a moment at thebottom, and was just going to step off when I remembered that I 'ad gotmy boots on, and I 'ad to go up agin and take 'em off.

I went down very slow the next time, and anybody who 'as been down aniron ladder with thin, cold rungs, in their bare feet, will know why,and I had just dipped my left foot in, when the wharf-bell rang.

I 'oped at fust that

it was a runaway-ring, but it kept on, and thelonger it kept on, the worse it got. I went up that ladder agin andcalled out that I was coming, and then I went into the office and justslipped on my coat and trousers and went to the gate.

"Wot d'you want?" I ses, opening the wicket three or four

_preview.jpg) Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection)

Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection) The Monkey's Paw

The Monkey's Paw Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II

Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II Odd Craft, Complete

Odd Craft, Complete The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection

The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection Deep Waters, the Entire Collection

Deep Waters, the Entire Collection Three at Table

Three at Table Light Freights

Light Freights Night Watches

Night Watches The Three Sisters

The Three Sisters Ship's Company, the Entire Collection

Ship's Company, the Entire Collection His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts

His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts Fine Feathers

Fine Feathers My Man Sandy

My Man Sandy Self-Help

Self-Help Captains All and Others

Captains All and Others Back to Back

Back to Back More Cargoes

More Cargoes Believe You Me!

Believe You Me! Keeping Up Appearances

Keeping Up Appearances The Statesmen Snowbound

The Statesmen Snowbound An Adulteration Act

An Adulteration Act The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches

The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches Husbandry

Husbandry Love and the Ironmonger

Love and the Ironmonger The Old Man's Bag

The Old Man's Bag Dirty Work

Dirty Work Easy Money

Easy Money The Lady of the Barge

The Lady of the Barge Bedridden and the Winter Offensive

Bedridden and the Winter Offensive Odd Charges

Odd Charges Friends in Need

Friends in Need Watch-Dogs

Watch-Dogs Cupboard Love

Cupboard Love Captains All

Captains All A Spirit of Avarice

A Spirit of Avarice The Nest Egg

The Nest Egg The Guardian Angel

The Guardian Angel The Convert

The Convert Captain Rogers

Captain Rogers Breaking a Spell

Breaking a Spell Striking Hard

Striking Hard The Bequest

The Bequest Shareholders

Shareholders The Weaker Vessel

The Weaker Vessel John Henry Smith

John Henry Smith Four Pigeons

Four Pigeons Made to Measure

Made to Measure For Better or Worse

For Better or Worse Fairy Gold

Fairy Gold Family Cares

Family Cares Good Intentions

Good Intentions Prize Money

Prize Money The Temptation of Samuel Burge

The Temptation of Samuel Burge The Madness of Mr. Lister

The Madness of Mr. Lister The Constable's Move

The Constable's Move Paying Off

Paying Off Double Dealing

Double Dealing A Mixed Proposal

A Mixed Proposal Bill's Paper Chase

Bill's Paper Chase The Changing Numbers

The Changing Numbers Over the Side

Over the Side Lawyer Quince

Lawyer Quince The White Cat

The White Cat Admiral Peters

Admiral Peters The Third String

The Third String The Vigil

The Vigil Bill's Lapse

Bill's Lapse His Other Self

His Other Self Matrimonial Openings

Matrimonial Openings The Substitute

The Substitute Deserted

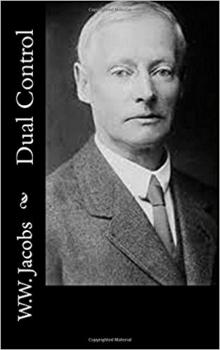

Deserted Dual Control

Dual Control Homeward Bound

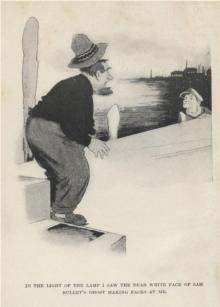

Homeward Bound Sam's Ghost

Sam's Ghost The Unknown

The Unknown Stepping Backwards

Stepping Backwards Sentence Deferred

Sentence Deferred The Persecution of Bob Pretty

The Persecution of Bob Pretty Skilled Assistance

Skilled Assistance A Golden Venture

A Golden Venture Establishing Relations

Establishing Relations A Tiger's Skin

A Tiger's Skin Bob's Redemption

Bob's Redemption Manners Makyth Man

Manners Makyth Man The Head of the Family

The Head of the Family The Understudy

The Understudy Odd Man Out

Odd Man Out Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary

Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence Blundell's Improvement

Blundell's Improvement The Toll-House

The Toll-House Dixon's Return

Dixon's Return Keeping Watch

Keeping Watch The Boatswain's Mate

The Boatswain's Mate The Castaway

The Castaway In the Library

In the Library The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre