- Home

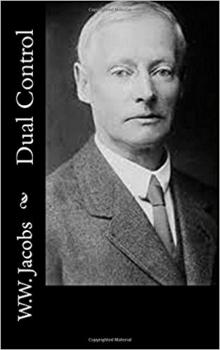

- W. W. Jacobs

The Nest Egg

The Nest Egg Read online

Produced by David Widger

CAPTAINS ALL

By W.W. Jacobs

THE NEST EGG

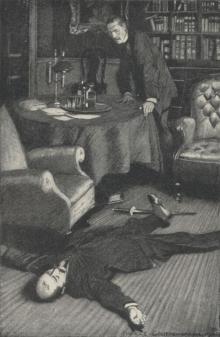

"The Nest Egg."]

"Artfulness," said the night-watch-man, smoking placidly, "is a gift; butit don't pay always. I've met some artful ones in my time--plenty of'em; but I can't truthfully say as 'ow any of them was the better formeeting me."

He rose slowly from the packing-case on which he had been sitting and,stamping down the point of a rusty nail with his heel, resumed his seat,remarking that he had endured it for some time under the impression thatit was only a splinter.

"I've surprised more than one in my time," he continued, slowly. "When Imet one of these 'ere artful ones I used fust of all to pretend to bemore stupid than wot I really am."

He stopped and stared fixedly.

"More stupid than I looked," he said. He stopped again.

"More stupid than wot they thought I looked," he said, speaking withmarked deliberation. And I'd let 'em go on and on until I thought I had'ad about enough, and then turn round on 'em. Nobody ever got the bettero' me except my wife, and that was only before we was married. Twonights arterwards she found a fish-hook in my trouser-pocket, and arterthat I could ha' left untold gold there--if I'd ha' had it. It spoiltwot some people call the honey-moon, but it paid in the long run.

One o' the worst things a man can do is to take up artfulness all of asudden. I never knew it to answer yet, and I can tell you of a casethat'll prove my words true.

It's some years ago now, and the chap it 'appened to was a young man, ashipmate o' mine, named Charlie Tagg. Very steady young chap he was, toosteady for most of 'em. That's 'ow it was me and 'im got to be suchpals.

He'd been saving up for years to get married, and all the advice we couldgive 'im didn't 'ave any effect. He saved up nearly every penny of 'ismoney and gave it to his gal to keep for 'im, and the time I'm speakingof she'd got seventy-two pounds of 'is and seventeen-and-six of 'er ownto set up house-keeping with.

Then a thing happened that I've known to 'appen to sailormen afore. AtSydney 'e got silly on another gal, and started walking out with her, andafore he knew wot he was about he'd promised to marry 'er too.

Sydney and London being a long way from each other was in 'is favour, butthe thing that troubled 'im was 'ow to get that seventy-two pounds out ofEmma Cook, 'is London gal, so as he could marry the other with it. Itworried 'im all the way home, and by the time we got into the Londonriver 'is head was all in a maze with it. Emma Cook 'ad got it all savedup in the bank, to take a little shop with when they got spliced, and 'owto get it he could not think.

He went straight off to Poplar, where she lived, as soon as the ship wasberthed. He walked all the way so as to 'ave more time for thinking, butwot with bumping into two old gentlemen with bad tempers, and beingnearly run over by a cabman with a white 'orse and red whiskers, he gotto the house without 'aving thought of anything.

They was just finishing their tea as 'e got there, and they all seemed sopleased to see 'im that it made it worse than ever for 'im. Mrs. Cook,who 'ad pretty near finished, gave 'im her own cup to drink out of, andsaid that she 'ad dreamt of 'im the night afore last, and old Cook saidthat he 'ad got so good-looking 'e shouldn't 'ave known him.

"I should 'ave passed 'im in the street," he ses. "I never see such analteration."

"They'll be a nice-looking couple," ses his wife, looking at a youngchap, named George Smith, that 'ad been sitting next to Emma.

Charlie Tagg filled 'is mouth with bread and butter, and wondered 'ow hewas to begin. He squeezed Emma's 'and just for the sake of keeping upappearances, and all the time 'e was thinking of the other gal waitingfor 'im thousands o' miles away.

"You've come 'ome just in the nick o' time," ses old Cook; "if you'd doneit o' purpose you couldn't 'ave arranged it better."

"Somebody's birthday?" ses Charlie, trying to smile.

Old Cook shook his 'ead. "Though mine is next Wednesday," he ses, "andthank you for thinking of it. No; you're just in time for the biggestbargain in the chandlery line that anybody ever 'ad a chance of. If you'adn't ha' come back we should have 'ad to ha' done it without you."

"Eighty pounds," ses Mrs. Cook, smiling at Charlie. "With the moneyEmma's got saved and your wages this trip you'll 'ave plenty. You mustcome round arter tea and 'ave a look at it."

"Little place not arf a mile from 'ere," ses old Cook. "Properly workedup, the way Emma'll do it, it'll be a little fortune. I wish I'd had achance like it in my young time."

He sat shaking his 'ead to think wot he'd lost, and Charlie Tagg satstaring at 'im and wondering wot he was to do.

"My idea is for Charlie to go for a few more v'y'ges arter they'remarried while Emma works up the business," ses Mrs. Cook; "she'll be allright with young Bill and Sarah Ann to 'elp her and keep 'er companywhile he's away."

"We'll see as she ain't lonely," ses George Smith, turning to Charlie.

Charlie Tagg gave a bit of a cough and said it wanted considering. Hesaid it was no good doing things in a 'urry and then repenting of 'em allthe rest of your life. And 'e said he'd been given to understand thatchandlery wasn't wot it 'ad been, and some of the cleverest people 'eknew thought that it would be worse before it was better. By the timehe'd finished they was all looking at 'im as though they couldn't believetheir ears.

"You just step round and 'ave a look at the place," ses old Cook; "ifthat don't make you alter your tune, call me a sinner."

Charlie Tagg felt as though 'e could ha' called 'im a lot o' worse thingsthan that, but he took up 'is hat and Mrs. Cook and Emma got theirbonnets on and they went round.

"I don't think much of it for eighty pounds," ses Charlie, beginning hisartfulness as they came near a big shop, with plate-glass and a doublefront.

"Eh?" ses old Cook, staring at 'im. "Why, that ain't the place. Why,you wouldn't get that for eight 'undred."

"Well, I don't think much of it," ses Charlie; "if it's worse than that Ican't look at it--I can't, indeed."

"You ain't been drinking, Charlie?" ses old Cook, in a puzzled voice.

"Certainly not," ses Charlie.

He was pleased to see 'ow anxious they all looked, and when they did cometo the shop 'e set up a laugh that old Cook said chilled the marrer in'is bones. He stood looking in a 'elpless sort o' way at his wife andEmma, and then at last he ses, "There it is; and a fair bargain at theprice."

"I s'pose you ain't been drinking?" ses Charlie.

"Wot's the matter with it?" ses Mrs. Cook flaring up.

"Come inside and look at it," ses Emma, taking 'old of his arm.

"Not me," ses Charlie, hanging back. "Why, I wouldn't take it at agift."

He stood there on the kerbstone, and all they could do 'e wouldn't budge.He said it was a bad road and a little shop, and 'ad got a look about ithe didn't like. They walked back 'ome like a funeral procession, andEmma 'ad to keep saying "_H's!_" in w'ispers to 'er mother all the way.

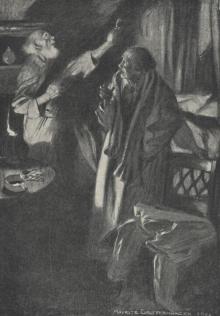

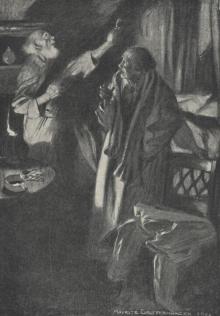

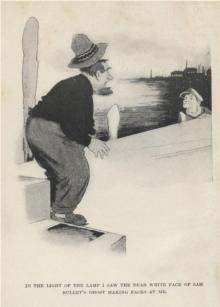

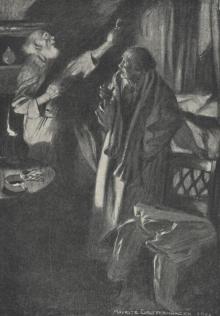

"He said it was a had road and a little shop, and 'ad gota look about it he didn't like."]

"I don't know wot Charlie does want, I'm sure," ses Mrs. Cook, taking off'er bonnet as soon as she got indoors and pitching it on the chair he wasjust going to set down on.

"It's so awk'ard," ses old Cook, rubbing his 'cad. "Fact is, Charlie, wepretty near gave 'em to understand as we'd buy it."

"It's as good as settled," ses Mrs. Cook, trembling all over with temper.

"They won't settle till they get the money," ses Charlie. "You may makeyour mind easy about that."

"Emma's drawn it all out of the bank ready," ses old Cook, eager like.

Charlie felt 'ot and cold all over. "I'd better take care of it," heses, in a trembling voice. "You might

be

_preview.jpg) Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection)

Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection) The Monkey's Paw

The Monkey's Paw Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II

Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II Odd Craft, Complete

Odd Craft, Complete The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection

The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection Deep Waters, the Entire Collection

Deep Waters, the Entire Collection Three at Table

Three at Table Light Freights

Light Freights Night Watches

Night Watches The Three Sisters

The Three Sisters Ship's Company, the Entire Collection

Ship's Company, the Entire Collection His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts

His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts Fine Feathers

Fine Feathers My Man Sandy

My Man Sandy Self-Help

Self-Help Captains All and Others

Captains All and Others Back to Back

Back to Back More Cargoes

More Cargoes Believe You Me!

Believe You Me! Keeping Up Appearances

Keeping Up Appearances The Statesmen Snowbound

The Statesmen Snowbound An Adulteration Act

An Adulteration Act The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches

The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches Husbandry

Husbandry Love and the Ironmonger

Love and the Ironmonger The Old Man's Bag

The Old Man's Bag Dirty Work

Dirty Work Easy Money

Easy Money The Lady of the Barge

The Lady of the Barge Bedridden and the Winter Offensive

Bedridden and the Winter Offensive Odd Charges

Odd Charges Friends in Need

Friends in Need Watch-Dogs

Watch-Dogs Cupboard Love

Cupboard Love Captains All

Captains All A Spirit of Avarice

A Spirit of Avarice The Nest Egg

The Nest Egg The Guardian Angel

The Guardian Angel The Convert

The Convert Captain Rogers

Captain Rogers Breaking a Spell

Breaking a Spell Striking Hard

Striking Hard The Bequest

The Bequest Shareholders

Shareholders The Weaker Vessel

The Weaker Vessel John Henry Smith

John Henry Smith Four Pigeons

Four Pigeons Made to Measure

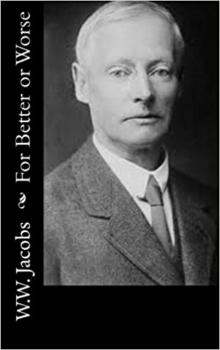

Made to Measure For Better or Worse

For Better or Worse Fairy Gold

Fairy Gold Family Cares

Family Cares Good Intentions

Good Intentions Prize Money

Prize Money The Temptation of Samuel Burge

The Temptation of Samuel Burge The Madness of Mr. Lister

The Madness of Mr. Lister The Constable's Move

The Constable's Move Paying Off

Paying Off Double Dealing

Double Dealing A Mixed Proposal

A Mixed Proposal Bill's Paper Chase

Bill's Paper Chase The Changing Numbers

The Changing Numbers Over the Side

Over the Side Lawyer Quince

Lawyer Quince The White Cat

The White Cat Admiral Peters

Admiral Peters The Third String

The Third String The Vigil

The Vigil Bill's Lapse

Bill's Lapse His Other Self

His Other Self Matrimonial Openings

Matrimonial Openings The Substitute

The Substitute Deserted

Deserted Dual Control

Dual Control Homeward Bound

Homeward Bound Sam's Ghost

Sam's Ghost The Unknown

The Unknown Stepping Backwards

Stepping Backwards Sentence Deferred

Sentence Deferred The Persecution of Bob Pretty

The Persecution of Bob Pretty Skilled Assistance

Skilled Assistance A Golden Venture

A Golden Venture Establishing Relations

Establishing Relations A Tiger's Skin

A Tiger's Skin Bob's Redemption

Bob's Redemption Manners Makyth Man

Manners Makyth Man The Head of the Family

The Head of the Family The Understudy

The Understudy Odd Man Out

Odd Man Out Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary

Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence Blundell's Improvement

Blundell's Improvement The Toll-House

The Toll-House Dixon's Return

Dixon's Return Keeping Watch

Keeping Watch The Boatswain's Mate

The Boatswain's Mate The Castaway

The Castaway In the Library

In the Library The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre