- Home

- W. W. Jacobs

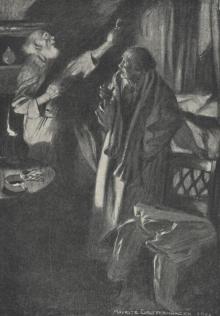

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre Read online

Academy Chicago Publishers

363 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

First published by Academy Chicago Publishers in 1997.

Reprinted in 2007.

© 1997 Academy Chicago Publishers

Introduction © 1997 Gary Hoppenstand

Printed and bound in the USA.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jacobs, W.W. (William Wymark), 1863-1943.

The Monkey’s Paw and other tales of mystery and the Macabre / W. W. Jacobs ; edited and with an introduction by Gary Hoppenstand.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-89733-441-9

1. Fantastic fiction, English. 2. Ghost stories, English. 3. Horror tales, English. 4. Supernatural—Fiction.

I. Hoppenstand, Gary. II. Title.

PR4821J2A6 1997

823’ .912—dc21

97-2988

CIP

To

– Doug Noverr –

with appreciation

Contents

Introduction

Selected Bibliography

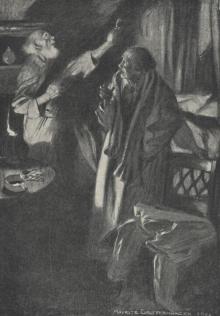

1 The Monkey’s Paw

2 The Well

3 The Three Sisters

4 The Toll-House

5 Jerry Bundler

6 His Brother’s Keeper

7 The Interruption

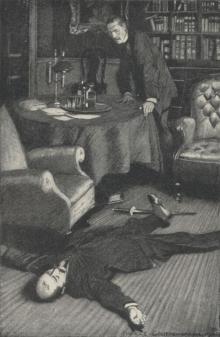

8 In the Library

9 Captain Rogers

10 The Lost Ship

11 Three at Table

12 The Brown Man’s Servant

13 Over the Side

14 The Vigil

15 Sam’s Ghost

16 In Mid-Atlantic

17 Twin Spirits

18 The Castaway

Introduction

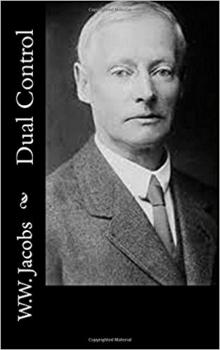

William Wymark Jacobs was born in London on September 8, 1863, into a modest working-class household. His father, William, was the manager of the South Devon Wharf; the family lived for a time at Wapping. Thus Jacobs had an early familiarity with sailors and dockworkers; he used these memories to create the stories that were to make his reputation. Despite his present identification chiefly as the author of “The Monkey’s Paw,” Jacobs in his time was famous and much respected as a writer of sea stories and as a humorist.

He was educated at private schools and at the age of sixteen, after passing a Civil Service examination, took his first job as a clerk in the Savings Bank Department of the General Post Office where, he later wrote, “for the sake of the pay envelope on the first of each month, I passed my days in captivity.” He attempted to enliven this captivity by writing. “From the age of twenty,” he noted, “I tried my hand at writing mostly humorous articles. It was a pleasant hobby and the more agreeable because it brought me a little extra pocket-money.”1 His first efforts appeared in Blackfriars Magazine, an “amateur journal” produced in the Savings Bank Department where he worked. It was, Jacobs says, when he was paid five shillings for a humorous article in the periodical Rare Bits, that he recognized his calling as a writer.s2 The bibliographer E.A. Osborne wrote of Jacobs’ early efforts that, although he had, from 1886 to 1894, “contributed thousands of words to professional papers, these had either appeared anonymously or over his initials, so that he had no reputation as a writer. The submission of some manuscripts to To-Day, of which Jerome K. Jerome was then the editor, was his real introduction to success in literature.”3

In 1896 he published Many Cargoes, his first collection of short fiction. This was an immediate success. Two other collections followed: The Skipper s Wooing (1897) and Sea Urchins (1898). Although Jacobs, like Arthur Conan Doyle, enjoyed a beneficial relationship with the popular Strand Magazine, which published nearly all his short fiction from 1897 on, it was only after the appearance of Sea Urchins that Jacobs felt secure enough to leave his position at the Post Office to become a full-time writer. He says, with typical self-deprecation:

It was not until I had been writing for some years for amusement and a little extra pocket-money that I began to write of the waterside…. Then the coastwise trips that I had taken in my youth came back to me with all the illusion of the past. Barges, schooners, little steamships and the dingy old wharf at Wapping on which I had lived for four years, took on a new appearance. They came as old friends and helped to push a lazy pen.4

Of Many Cargoes, the critic C. Lewis Hind wrote: “Few books are welcomed with such gusts of praise….It is impossible not to laugh when Jacobs means us to laugh. He never bores the reader. He makes pictures but he ignores scenery…. His sentiment is austere, and he has no sense of tears.”5 Hind also wrote an interesting sketch of Jacobs:

In the late nineties sometimes I met at literary gatherings … a slight, slim, unobtrusive young man, fair and clean-shaven, with observant eyes, whose way it was to hover shyly on the outskirts of the crowd. He did not make much impression on me: he never said anything particularly witty or tender: we just nodded, but I always seemed to know that this hovering, unobtrusive man was present. He wrote, I was told, funny little stories about sailormen.6

Evelyn Waugh, whose brother Alec married Jacobs’ eldest child Barbara, described Jacobs as “wan, skinny, sharp-faced, with watery eyes.” But within this “drab facade,” Waugh found, “lurked a pure artist.”7

In short, from the late nineteenth through the early twentieth century, W. W. Jacobs was the undisputed master of the English humorous short story. It is ironic that today he is known only as the author of the macabre masterpiece, “The Monkey’s Paw.” This tale, it has been said, “of superstition and terror unfolding within a realistic setting of domestic warmth and coziness, is an example of Jacobs’ ability to combine everyday life and gentle humor with exotic adventure and dread.”8 But this is not to say that his macabre fiction was not appreciated in his own time. G.K. Chesterton wrote that these stories “stand alone among our modern tales of terror in the fact that they are dignified and noble. They rise out of terror into awe…. His humour is wild, but it is sane humour. His horror is wild, but it is a sane horror.”9

In 1931 Snug Harbor, an omnibus collection of Jacobs’ work, was published. By that time Jacobs had turned his creative attention to the theatre. He wrote some seventeen plays, most of them in collaboration with other playwrights. His life was somewhat restricted in his later years. His marriage was apparently not a happy one: his wife, Agnes Eleanor Williams, was much younger than he, described by Evelyn Waugh as “an earnest and effusive Welshwoman who had done time for breaking windows as a suffragette.”10 Jacobs himself was politically conservative.

He died on September 1, 1943, in a London nursing home.

Jacobs’ macabre fiction is notable because, firstly, of its use of simple, effective language. He does not attempt complex characterization or settings; nothing is allowed to hamper the swift flow of the plot. In addition, the reader is forced to use his imagination to supply certain details, to be involved—an ideal requirement for a short tale of terror. Secondly, Jacobs is a master of irony who enjoys leading his reader to expect a certain denouement and then surprising him with another. Few actual ghosts prowl the dim corridors of Jacobs’ haunted houses. Often his characters themselves become their own worst nightmares, trapped by guilt or doomed by superstition. Jacobs’ portrayal of evil is problematic enough to make his work appealing to the modern reader. And, finally, his work frequently contains his unique brand of humor—which was, in his lifetime, considered his important artis

tic achievement.

Today, his humorous work is all but forgotten, and it is “The Monkey’s Paw” which has guaranteed immortality for him. But, as you will undoubtedly observe as you read this collection, W. W. Jacobs deserves recognition for far more than that. Let us hope this book will help to widen appreciation of his accomplishments.

Notes to the Introduction

1. “Jacobs, William Wymark,” Twentieth Century Authors: A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Literature, 1966 ed.

2. E.A. Osborne, “Epitome of a Bibliography of W. W. Jacobs,” The Bookman 86 (1934): 99.

3. Osborne, 101.

4. Osborne, 99-100.

5. C. Lewis Hind, More Authors and I (London: John Lane at the Bodley Head, 1922), 171-72.

6. Hind, 170.

7. Evelyn Waugh, A Little Learning: An Autobiography (Boston: Little, Brown, 1964), 118.

8. Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of Literature (1995), 595.

9. G.K. Chesterton, A Handful of Authors: Essays on Books & Writers, ed. Dorothy Collins (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1953), 35.

10. Waugh, 118.

Selected Bibliography of W. W. Jacobs

– Fiction –

Many Cargoes (1896): collection

The Skipper s Wooing & The Brown Man s Servant (1897): two novellas

Sea Urchins (1898; also titled More Cargoes): collection

A Master of Craft (1900): novel

Light Freights (1901): collection

At Sunwich Port (1902): novel

The Lady of the Barge (1902): collection

Odd Craft (1903): collection

Dialstone Lane (1904): novel

Captains All (1905): collection

Short Cruises (1907): collection

Salthaven (1908): novel

Sailor’s Knots (1909): collection

Ship’s Company (1911): collection

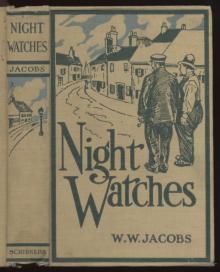

Night Watches (1914): collection

The Castaways (1916): novel

Deep Waters (1919): collection

Sea Whispers (1926): collection

– Drama –

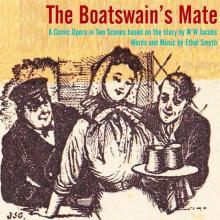

The Boatswain s Mate (1907): with H.C. Sargent

The Grey Parrot (1908): with Charles Rock

The Ghost of Jerry Bundler (1908): with Charles Rock

The Changeling (1908): with H.C. Sargent

Admiral Peters (1909): with Horace Mills

The Monkey’s Paw (1910): adapted by Louis N. Parker

Beauty and the Barge (1910): with Louis N. Parker

A Love Passage (1913): with P.E. Hubbard

In the Library (1913): with H.C. Sargent

Keeping Up Appearances (1919)

The Castaway (1924): with H.C. Sargent

Establishing Relations (1925)

The Warming Pan (1929)

A Distant Relative (1930)

Master Mariners (1930)

Matrimonial Openings (1931)

Dixon’s Return (1931)

Double Dealing (1935)

1

The Monkey’s Paw

– I –

Without, the night was cold and wet, but in the small parlour of Laburnam Villa the blinds were drawn and the fire burned brightly. Father and son were at chess, the former, who possessed ideas about the game involving radical changes, putting his king into such sharp and unnecessary perils that it even provoked comment from the white-haired old lady knitting placidly by the fire.

“Hark at the wind,” said Mr White, who, having seen a fatal mistake after it was too late, was amiably desirous of preventing his son from seeing it.

“I’m listening,” said the latter, grimly surveying the board as he stretched out his hand. “Check.”

“I should hardly think that he’d come tonight,” said his father, with his hand poised over the board.

“Mate,” replied the son.

“That’s the worst of living so far out,” bawled Mr White, with sudden and unlooked-for violence; “of all the beastly, slushy, out-of-the-way places to live in, this is the worst. Pathway’s a bog, and the road’s a torrent. I don’t know what people are thinking about. I suppose because only two houses in the road are let, they think it doesn’t matter.”

“Never mind, dear,” said his wife, soothingly; “perhaps you’ll win the next one.”

Mr White looked up sharply, just in time to intercept a knowing glance between mother and son. The words died away on his lips, and he hid a guilty grin in his thin grey beard.

“There he is,” said Herbert White, as the gate banged to loudly and heavy footsteps came toward the door.

The old man rose with hospitable haste, and opening the door, was heard condoling with the new arrival. The new arrival also condoled with himself, so that Mrs White said, “Tut, tut!” and coughed gently as her husband entered the room, followed by a tall, burly man, beady of eye and rubicund of visage.

“Sergeant-Major Morris,” he said, introducing him.

The sergeant-major shook hands, and taking the proffered seat by the fire, watched contentedly while his host got out whiskey and tumblers and stood a small copper kettle on the fire.

At the third glass his eyes got brighter, and he began to talk, the little family circle regarding with eager interest this visitor from distant parts, as he squared his broad shoulders in the chair and spoke of wild scenes and doughty deeds; of wars and plagues and strange peoples.

“Twenty-one years of it,” said Mr White, nodding at his wife and son. “When he went away he was a slip of a youth in the warehouse. Now look at him.”

“He don’t look to have taken much harm,” said Mrs White, politely.

“I’d like to go to India myself,” said the old man, “just to look round a bit, you know.”

“Better where you are,” said the sergeant-major, shaking his head. He put down the empty glass, and sighing softly, shook it again.

“I should like to see those old temples and fakirs and jugglers,” said the old man. “What was that you started telling me the other day about a monkey’s paw or something, Morris?”

“Nothing,” said the soldier, hastily. “Leastways nothing worth hearing.”

“Monkey’s paw?” said Mrs White, curiously.

“Well, it’s just a bit of what you might call magic, perhaps,” said the sergeant-major, off-handedly.

His three listeners leaned forward eagerly. The visitor absent-mindedly put his empty glass to his lips and then set it down again. His host filled it for him.

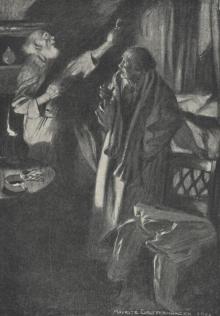

“To look at,” said the sergeant-major, fumbling in his pocket, “it’s just an ordinary little paw, dried to a mummy.”

He took something out of his pocket and proffered it. Mrs White drew back with a grimace, but her son, taking it, examined it curiously.

“And what is there special about it?” inquired Mr White as he took it from his son, and having examined it, placed it upon the table.

“It had a spell put on it by an old fakir,” said the sergeant-major, “a very holy man. He wanted to show that fate ruled people’s lives, and that those who interfered with it did so to their sorrow. He put a spell on it so that three separate men could each have three wishes from it.”

His manner was so impressive that his hearers were conscious that their light laughter jarred somewhat.

“Well, why don’t you have three, sir?” said Herbert White, cleverly.

The soldier regarded him in the way that middle age is wont to regard presumptuous youth. “I have,” he said, quietly, and his blotchy face whitened.

“And did you really have the three wishes granted?” asked Mrs White.

“I did,” said the sergeant-major, and his glass tapped against his strong teeth.

“And has anybody else wished?” persisted the old lady.

“The first man had his three wishes. Yes,” was the reply; “I don’t know what the first two were, but the third was for death. That’s how I got the paw.”

His tones were so grave that a hush fell upon the group.

“If you’

ve had your three wishes, it’s no good to you now, then, Morris,” said the old man at last. “What do you keep it for?”

The soldier shook his head. “Fancy, I suppose,” he said, slowly. “I did have some idea of selling it, but I don’t think I will. It has caused enough mischief already. Besides, people won’t buy. They think it’s a fairy tale; some of them, and those who do think anything of it want to try it first and pay me afterward.”

“If you could have another three wishes,” said the old man, eyeing him keenly, “would you have them?”

“I don’t know,” said the other. “I don’t know.”

He took the paw, and dangling it between his forefinger and thumb, suddenly threw it upon the fire. White, with a slight cry, stooped down and snatched it off.

“Better let it burn,” said the soldier, solemnly.

“If you don’t want it, Morris,” said the other, “give it to me.”

“I won’t,” said his friend, doggedly. “I threw it on the fire. If you keep it, don’t blame me for what happens. Pitch it on the fire again like a sensible man.”

The other shook his head and examined his new possession closely. “How do you do it?” he inquired.

“Hold it up in your right hand and wish aloud,” said the sergeant-major, “but I warn you of the consequences.”

“Sounds like the Arabian Nights” said Mrs White, as she rose and began to set the supper. “Don’t you think you might wish for four pairs of hands for me?”

Her husband drew the talisman from pocket, and then all three burst into laughter as the sergeant-major, with a look of alarm on his face, caught him by the arm.

“If you must wish,” he said, gruffly, “wish for something sensible.”

Mr White dropped it back in his pocket, and placing chairs, motioned his friend to the table. In the business of supper the talisman was partly forgotten, and afterward the three sat listening in an enthralled fashion to a second instalment of the soldier’s adventures in India.

“If the tale about the monkey’s paw is not more truthful than those he has been telling us,” said Herbert, as the door closed behind their guest, just in time for him to catch the last train, “we sha’nt make much out of it.”

_preview.jpg) Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection)

Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection) The Monkey's Paw

The Monkey's Paw Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II

Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II Odd Craft, Complete

Odd Craft, Complete The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection

The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection Deep Waters, the Entire Collection

Deep Waters, the Entire Collection Three at Table

Three at Table Light Freights

Light Freights Night Watches

Night Watches The Three Sisters

The Three Sisters Ship's Company, the Entire Collection

Ship's Company, the Entire Collection His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts

His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts Fine Feathers

Fine Feathers My Man Sandy

My Man Sandy Self-Help

Self-Help Captains All and Others

Captains All and Others Back to Back

Back to Back More Cargoes

More Cargoes Believe You Me!

Believe You Me! Keeping Up Appearances

Keeping Up Appearances The Statesmen Snowbound

The Statesmen Snowbound An Adulteration Act

An Adulteration Act The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches

The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches Husbandry

Husbandry Love and the Ironmonger

Love and the Ironmonger The Old Man's Bag

The Old Man's Bag Dirty Work

Dirty Work Easy Money

Easy Money The Lady of the Barge

The Lady of the Barge Bedridden and the Winter Offensive

Bedridden and the Winter Offensive Odd Charges

Odd Charges Friends in Need

Friends in Need Watch-Dogs

Watch-Dogs Cupboard Love

Cupboard Love Captains All

Captains All A Spirit of Avarice

A Spirit of Avarice The Nest Egg

The Nest Egg The Guardian Angel

The Guardian Angel The Convert

The Convert Captain Rogers

Captain Rogers Breaking a Spell

Breaking a Spell Striking Hard

Striking Hard The Bequest

The Bequest Shareholders

Shareholders The Weaker Vessel

The Weaker Vessel John Henry Smith

John Henry Smith Four Pigeons

Four Pigeons Made to Measure

Made to Measure For Better or Worse

For Better or Worse Fairy Gold

Fairy Gold Family Cares

Family Cares Good Intentions

Good Intentions Prize Money

Prize Money The Temptation of Samuel Burge

The Temptation of Samuel Burge The Madness of Mr. Lister

The Madness of Mr. Lister The Constable's Move

The Constable's Move Paying Off

Paying Off Double Dealing

Double Dealing A Mixed Proposal

A Mixed Proposal Bill's Paper Chase

Bill's Paper Chase The Changing Numbers

The Changing Numbers Over the Side

Over the Side Lawyer Quince

Lawyer Quince The White Cat

The White Cat Admiral Peters

Admiral Peters The Third String

The Third String The Vigil

The Vigil Bill's Lapse

Bill's Lapse His Other Self

His Other Self Matrimonial Openings

Matrimonial Openings The Substitute

The Substitute Deserted

Deserted Dual Control

Dual Control Homeward Bound

Homeward Bound Sam's Ghost

Sam's Ghost The Unknown

The Unknown Stepping Backwards

Stepping Backwards Sentence Deferred

Sentence Deferred The Persecution of Bob Pretty

The Persecution of Bob Pretty Skilled Assistance

Skilled Assistance A Golden Venture

A Golden Venture Establishing Relations

Establishing Relations A Tiger's Skin

A Tiger's Skin Bob's Redemption

Bob's Redemption Manners Makyth Man

Manners Makyth Man The Head of the Family

The Head of the Family The Understudy

The Understudy Odd Man Out

Odd Man Out Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary

Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence Blundell's Improvement

Blundell's Improvement The Toll-House

The Toll-House Dixon's Return

Dixon's Return Keeping Watch

Keeping Watch The Boatswain's Mate

The Boatswain's Mate The Castaway

The Castaway In the Library

In the Library The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre