- Home

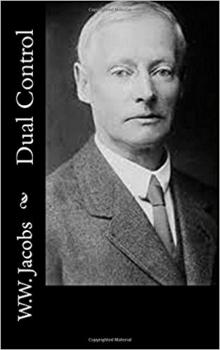

- W. W. Jacobs

Cupboard Love

Cupboard Love Read online

Produced by David Widger

THE LADY OF THE BARGE

AND OTHER STORIES

By W. W. Jacobs

CUPBOARD LOVE

In the comfortable living-room at Negget's farm, half parlour and halfkitchen, three people sat at tea in the waning light of a Novemberafternoon. Conversation, which had been brisk, had languished somewhat,owing to Mrs. Negget glancing at frequent intervals toward the door,behind which she was convinced the servant was listening, and checkingthe finest periods and the most startling suggestions with a warning_'ssh!_

"Go on, uncle," she said, after one of these interruptions.

"I forget where I was," said Mr. Martin Bodfish, shortly.

"Under our bed," Mr. Negget reminded him.

"Yes, watching," said Mrs. Negget, eagerly.

It was an odd place for an ex-policeman, especially as a small legacyadded to his pension had considerably improved his social position, butMr. Bodfish had himself suggested it in the professional hope that theperson who had taken Mrs. Negget's gold brooch might try for furtherloot. He had, indeed, suggested baiting the dressing-table with thefarmer's watch, an idea which Mr. Negget had promptly vetoed.

"I can't help thinking that Mrs. Pottle knows something about it," saidMrs. Negget, with an indignant glance at her husband.

"Mrs. Pottle," said the farmer, rising slowly and taking a seat on theoak settle built in the fireplace, "has been away from the village fornear a fortnit."

"I didn't say she took it," snapped his wife. "I said I believe sheknows something about it, and so I do. She's a horrid woman. Look atthe way she encouraged her girl Looey to run after that young travellerfrom Smithson's. The whole fact of the matter is, it isn't your brooch,so you don't care."

"I said--" began Mr. Negget.

"I know what you said," retorted his wife, sharply, "and I wish you'd bequiet and not interrupt uncle. Here's my uncle been in the policetwenty-five years, and you won't let him put a word in edgeways.'

"My way o' looking at it," said the ex-policeman, slowly, "is differentto that o' the law; my idea is, an' always has been, that everybody isguilty until they've proved their innocence."

"It's a wonderful thing to me," said Mr. Negget in a low voice to hispipe, "as they should come to a house with a retired policeman living init. Looks to me like somebody that ain't got much respect for thepolice."

The ex-policeman got up from the table, and taking a seat on the settleopposite the speaker, slowly filled a long clay and took a spill from thefireplace. His pipe lit, he turned to his niece, and slowly bade her goover the account of her loss once more.

"I missed it this morning," said Mrs. Negget, rapidly, "at ten minutespast twelve o'clock by the clock, and half-past five by my watch whichwants looking to. I'd just put the batch of bread into the oven, andgone upstairs and opened the box that stands on my drawers to get alozenge, and I missed the brooch."

"Do you keep it in that box?" asked the ex-policeman, slowly.

"Always," replied his niece. "I at once came down stairs and told Emmathat the brooch had been stolen. I said that I named no names, anddidn't wish to think bad of anybody, and that if I found the brooch backin the box when I went up stairs again, I should forgive whoever tookit."

"And what did Emma say?" inquired Mr. Bodfish.

"Emma said a lot o' things," replied Mrs. Negget, angrily. "I'm sure bythe lot she had to say you'd ha' thought she was the missis and me theservant. I gave her a month's notice at once, and she went straight upstairs and sat on her box and cried."

"Sat on her box?" repeated the ex-constable, impressively. "Oh!"

"That's what I thought," said his niece, "but it wasn't, because I gother off at last and searched it through and through. I never sawanything like her clothes in all my life. There was hardly a button or atape on; and as for her stockings--"

"She don't get much time," said Mr. Negget, slowly.

"That's right; I thought you'd speak up for her," cried his wife,shrilly.

"Look here--" began Mr. Negget, laying his pipe on the seat by his sideand rising slowly.

"Keep to the case in hand," said the ex-constable, waving him back to hisseat again. "Now, Lizzie."

"I searched her box through and through," said his niece, "but it wasn'tthere; then I came down again and had a rare good cry all to myself."

"That's the best way for you to have it," remarked Mr. Negget, feelingly.

Mrs. Negget's uncle instinctively motioned his niece to silence, andholding his chin in his hand, scowled frightfully in the intensity ofthought.

"See a cloo?" inquired Mr. Negget, affably.

"You ought to be ashamed of yourself, George," said his wife, angrily;"speaking to uncle when he's looking like that."

Mr. Bodfish said nothing; it is doubtful whether he even heard theseremarks; but he drew a huge notebook from his pocket, and after vainlytrying to point his pencil by suction, took a knife from the table andhastily sharpened it.

"Was the brooch there last night?" he inquired.

"It were," said Mr. Negget, promptly. "Lizzie made me get up just as theowd clock were striking twelve to get her a lozenge."

"It seems pretty certain that the brooch went since then," mused Mr.Bodfish.

"It would seem like it to a plain man," said Mr. Negget, guardedly.

"I should like to see the box," said Mr. Bodfish.

Mrs. Negget went up and fetched it and stood eyeing him eagerly as heraised the lid and inspected the contents. It contained only a fewlozenges and some bone studs. Mr. Negget helped himself to a lozenge,and going back to his seat, breathed peppermint.

"Properly speaking, that ought not to have been touched," said theex-constable, regarding him with some severity.

"Eh!" said the startled farmer, putting his finger to his lips.

"Never mind," said the other, shaking his head. "It's too late now."

"He doesn't care a bit," said Mrs. Negget, somewhat sadly. "He used tokeep buttons in that box with the lozenges until one night he gave me oneby mistake. Yes, you may laugh--I'm glad you can laugh."

Mr. Negget, feeling that his mirth was certainly ill-timed, shook forsome time in a noble effort to control himself, and despairing at length,went into the back place to recover. Sounds of blows indicative of Emmaslapping him on the back did not add to Mrs. Negget's serenity.

"The point is," said the ex-constable, "could anybody have come into yourroom while you was asleep and taken it?"

"No," said Mrs. Negget, decisively. I'm a very poor sleeper, and I'dhave woke at once, but if a flock of elephants was to come in the roomthey wouldn't wake George. He'd sleep through anything."

"Except her feeling under my piller for her handkerchief," corroboratedMr. Negget, returning to the sitting-room.

Mr. Bodfish waved them to silence, and again gave way to deep thought.Three times he took up his pencil, and laying it down again, sat anddrummed on the table with his fingers. Then he arose, and with bent headwalked slowly round and round the room until he stumbled over a stool.

"Nobody came to the house this morning, I suppose?" he said at length,resuming his seat.

"Only Mrs. Driver," said his niece.

"What time did she come?" inquired Mr. Bodfish.

"Here! look here!" interposed Mr. Negget. "I've known Mrs. Driverthirty year a'most."

"What time did she come?" repeated the ex-constable, pitilessly.

His niece shook her head. "It might have been eleven, and again it mighthave been earlier," she replied. "I was out when she came."

"Out!" almost shouted the other.

Mrs. Negget nodded.

"She was sitting in here when I came back."

Her uncle looked u

p and glanced at the door behind which a smallstaircase led to the room above.

"What was to prevent Mrs. Driver going up there while you were away?" hedemanded.

"I shouldn't like to think that of Mrs. Driver," said his niece, shakingher head; "but then in these days one never knows what might happen.Never. I've given up thinking about it. However, when I came back, Mrs.Driver was here, sitting in that very chair you are sitting in

_preview.jpg) Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection)

Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection) The Monkey's Paw

The Monkey's Paw Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II

Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II Odd Craft, Complete

Odd Craft, Complete The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection

The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection Deep Waters, the Entire Collection

Deep Waters, the Entire Collection Three at Table

Three at Table Light Freights

Light Freights Night Watches

Night Watches The Three Sisters

The Three Sisters Ship's Company, the Entire Collection

Ship's Company, the Entire Collection His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts

His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts Fine Feathers

Fine Feathers My Man Sandy

My Man Sandy Self-Help

Self-Help Captains All and Others

Captains All and Others Back to Back

Back to Back More Cargoes

More Cargoes Believe You Me!

Believe You Me! Keeping Up Appearances

Keeping Up Appearances The Statesmen Snowbound

The Statesmen Snowbound An Adulteration Act

An Adulteration Act The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches

The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches Husbandry

Husbandry Love and the Ironmonger

Love and the Ironmonger The Old Man's Bag

The Old Man's Bag Dirty Work

Dirty Work Easy Money

Easy Money The Lady of the Barge

The Lady of the Barge Bedridden and the Winter Offensive

Bedridden and the Winter Offensive Odd Charges

Odd Charges Friends in Need

Friends in Need Watch-Dogs

Watch-Dogs Cupboard Love

Cupboard Love Captains All

Captains All A Spirit of Avarice

A Spirit of Avarice The Nest Egg

The Nest Egg The Guardian Angel

The Guardian Angel The Convert

The Convert Captain Rogers

Captain Rogers Breaking a Spell

Breaking a Spell Striking Hard

Striking Hard The Bequest

The Bequest Shareholders

Shareholders The Weaker Vessel

The Weaker Vessel John Henry Smith

John Henry Smith Four Pigeons

Four Pigeons Made to Measure

Made to Measure For Better or Worse

For Better or Worse Fairy Gold

Fairy Gold Family Cares

Family Cares Good Intentions

Good Intentions Prize Money

Prize Money The Temptation of Samuel Burge

The Temptation of Samuel Burge The Madness of Mr. Lister

The Madness of Mr. Lister The Constable's Move

The Constable's Move Paying Off

Paying Off Double Dealing

Double Dealing A Mixed Proposal

A Mixed Proposal Bill's Paper Chase

Bill's Paper Chase The Changing Numbers

The Changing Numbers Over the Side

Over the Side Lawyer Quince

Lawyer Quince The White Cat

The White Cat Admiral Peters

Admiral Peters The Third String

The Third String The Vigil

The Vigil Bill's Lapse

Bill's Lapse His Other Self

His Other Self Matrimonial Openings

Matrimonial Openings The Substitute

The Substitute Deserted

Deserted Dual Control

Dual Control Homeward Bound

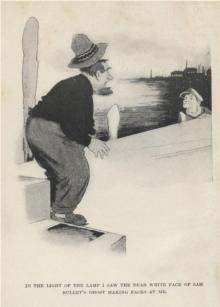

Homeward Bound Sam's Ghost

Sam's Ghost The Unknown

The Unknown Stepping Backwards

Stepping Backwards Sentence Deferred

Sentence Deferred The Persecution of Bob Pretty

The Persecution of Bob Pretty Skilled Assistance

Skilled Assistance A Golden Venture

A Golden Venture Establishing Relations

Establishing Relations A Tiger's Skin

A Tiger's Skin Bob's Redemption

Bob's Redemption Manners Makyth Man

Manners Makyth Man The Head of the Family

The Head of the Family The Understudy

The Understudy Odd Man Out

Odd Man Out Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary

Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence Blundell's Improvement

Blundell's Improvement The Toll-House

The Toll-House Dixon's Return

Dixon's Return Keeping Watch

Keeping Watch The Boatswain's Mate

The Boatswain's Mate The Castaway

The Castaway In the Library

In the Library The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre