- Home

- W. W. Jacobs

Ship's Company, the Entire Collection Page 11

Ship's Company, the Entire Collection Read online

Page 11

THE OLD MAN OF THE SEA

"What I want you to do," said Mr. George Wright, as he leaned towards theold sailor, "is to be an uncle to me."

"Aye, aye," said the mystified Mr. Kemp, pausing with a mug of beermidway to his lips.

"A rich uncle," continued the young man, lowering his voice to preventany keen ears in the next bar from acquiring useless knowledge. "Anuncle from New Zealand, who is going to leave me all 'is money."

"Where's it coming from?" demanded Mr. Kemp, with a little excitement.

"It ain't coming," was the reply. "You've only got to say you've got it.Fact of the matter is, I've got my eye on a young lady; there's anotherchap after 'er too, and if she thought I'd got a rich uncle it might makeall the difference. She knows I 'ad an uncle that went to New Zealandand was never heard of since. That's what made me think of it."

Mr. Kemp drank his beer in thoughtful silence. "How can I be a richuncle without any brass?" he inquired at length.

"I should 'ave to lend you some--a little," said Mr. Wright.

"What I want you to do," said Mr. George Wright, "is tobe an uncle to me."]

The old man pondered. "I've had money lent me before," he said,candidly, "but I can't call to mind ever paying it back. I always meantto, but that's as far as it got."

"It don't matter," said the other. "It'll only be for a little while,and then you'll 'ave a letter calling you back to New Zealand. See? Andyou'll go back, promising to come home in a year's time, after you'vewound up your business, and leave us all your money. See?"

Mr. Kemp scratched the back of his neck. "But she's sure to find it outin time," he objected.

"P'r'aps," said Mr. Wright. "And p'r'aps not. There'll be plenty oftime for me to get married before she does, and you could write back andsay you had got married yourself, or given your money to a hospital."

He ordered some more beer for Mr. Kemp, and in a low voice gave him asmuch of the family history as he considered necessary.

"I've only known you for about ten days," he concluded, "but I'd soonertrust you than people I've known for years."

"I took a fancy to you the moment I set eyes on you," rejoined Mr. Kemp."You're the living image of a young fellow that lent me five pounds once,and was drowned afore my eyes the week after. He 'ad a bit of a squint,and I s'pose that's how he came to fall overboard."

He emptied his mug, and then, accompanied by Mr. Wright, fetched hissea-chest from the boarding-house where he was staying, and took it tothe young man's lodgings. Fortunately for the latter's pocket the chestcontained a good best suit and boots, and the only expenses incurredwere for a large, soft felt hat and a gilded watch and chain. Dressedin his best, with a bulging pocket-book in his breast-pocket, he set outwith Mr. Wright on the following evening to make his first call.

Mr. Wright, who was also in his best clothes, led the way to a smalltobacconist's in a side street off the Mile End Road, and, raising hishat with some ceremony, shook hands with a good-looking young woman whostood behind the counter: Mr. Kemp, adopting an air of scornful dignityintended to indicate the possession of great wealth, waited.

"This is my uncle," said Mr. Wright, speaking rapidly, "from New Zealand,the one I spoke to you about. He turned up last night, and you mighthave knocked me down with a feather. The last person in the world Iexpected to see."

Mr. Kemp, in a good rolling voice, said, "Good evening, miss; I hope youare well," and, subsiding into a chair, asked for a cigar. His surprisewhen he found that the best cigar they stocked only cost sixpence almostassumed the dimensions of a grievance.

"It'll do to go on with," he said, smelling it suspiciously. "Have yougot change for a fifty-pound note?"

Miss Bradshaw, concealing her surprise by an effort, said that she wouldsee, and was scanning the contents of a drawer, when Mr. Kemp in somehaste discovered a few odd sovereigns in his waistcoat-pocket. Fiveminutes later he was sitting in the little room behind the shop, holdingforth to an admiring audience.

"So far as I know," he said, in reply to a question of Mrs. Bradshaw's,"George is the only relation I've got. Him and me are quite alone, and Ican tell you I was glad to find him."

Mrs. Bradshaw sighed. "It's a pity you are so far apart," she said.

"It's not for long," said Mr. Kemp. "I'm just going back for about ayear to wind up things out there, and then I'm coming back to leave myold bones over here. George has very kindly offered to let me live withhim."

"He won't suffer for it, I'll be bound," said Mrs. Bradshaw, archly.

"So far as money goes he won't," said the old man. "Not that that wouldmake any difference to George."

"It would be the same to me if you hadn't got a farthing," said Mr.Wright, promptly.

"It'll do to go on with," he said]

Mr. Kemp, somewhat affected, shook hands with him, and leaning back inthe most comfortable chair in the room, described his life and strugglesin New Zealand. Hard work, teetotalism, and the simple life combinedappeared to be responsible for a fortune which he affected to be too oldto enjoy. Misunderstandings of a painful nature were avoided by a timelyadmission that under medical advice he was now taking a fair amount ofstimulant.

"'Ow much did you say you'd got in the bank?"]

"Mind," he said, as he walked home with the elated George, "it's yourgame, not mine, and it's sure to come a bit expensive. I can't be a richuncle without spending a bit. 'Ow much did you say you'd got in thebank?"

"We must be as careful as we can," said Mr. Wright, hastily. "One thingis they can't leave the shop to go out much. It's a very good littlebusiness, and it ought to be all right for me and Bella one of thesedays, eh?"

Mr. Kemp, prompted by a nudge in the ribs, assented. "It's wonderful howthey took it all in about me," he said; "but I feel certain in my ownmind that I ought to chuck some money about."

"Tell 'em of the money you have chucked about," said Mr. Wright. "It'lldo just as well, and come a good deal cheaper. And you had better goround alone to-morrow evening. It'll look better. Just go in foranother one of their sixpenny cigars."

Mr. Kemp obeyed, and the following evening, after sitting a little whilechatting in the shop, was invited into the parlour, where, mindful of Mr.Wright's instructions, he held his listeners enthralled by tales of pastexpenditure. A tip of fifty pounds to his bedroom steward coming overwas characterized by Mrs. Bradshaw as extravagant.

"Seems to be going all right," said Mr. Wright, as the old man made hisreport; "but be careful; don't go overdoing it."

Mr. Kemp nodded. "I can turn 'em round my little finger," he said."You'll have Bella all to yourself to-morrow evening."

Mr. Wright flushed. "How did you manage that?" he inquired. "It's thefirst time she has ever been out with me alone."

"She ain't coming out," said Mr. Kemp. "She's going to stay at home andmind the shop; it's the mother what's coming out. Going to spend theevening with me!"

Mr. Wright frowned. "What did you do that for?" he demanded, hotly.

"I didn't do it," said Mr. Kemp, equably; "they done it. The old ladysays that, just for once in her life, she wants to see how it feels tospend money like water."

"_Money like water!_" repeated the horrified Mr. Wright. "Money like--I'll 'money' her--I'll----"

"It don't matter to me," said Mr. Kemp. "I can have a headache or achill, or something of that sort, if you like. I don't want to go. It'sno pleasure to me."

"What will it cost?" demanded Mr. Wright, pacing up and down the room.

The rich uncle made a calculation. "She wants to go to a place calledthe Empire," he said, slowly, "and have something for supper, and there'dbe cabs and things. I dessay it would cost a couple o' pounds, and itmight be more. But I'd just as soon ave' a chill--just."

Mr. Wright groaned, and after talking of Mrs. Bradshaw as though she werealready his mother-in-law, produced the money. His instructions as toeconomy lasted almost up to the moment when he stood wi

th Bella outsidethe shop on the following evening and watched the couple go off.

"It's wonderful how well they get on together," said Bella, as theyre-entered the shop and passed into the parlour. "I've never seen mothertake to anybody so quick as she has to him."

"I hope you like him, too," said Mr. Wright.

"He's a dear," said Bella. "Fancy having all that money. I wonder whatit feels like?"

"I suppose I shall know some day," said the young man, slowly; "but itwon't be much good to me unless----"

"Unless?" said Bella, after a pause.

"Unless it gives me what I want," replied the other. "I'd sooner be apoor man and married to the girl I love, than a millionaire."

Miss Bradshaw stole an uneasy glance at his somewhat sallow features, andbecame thoughtful.

"It's no good having diamonds and motor-cars and that sort of thingunless you have somebody to share them with," pursued Mr. Wright.

Miss Bradshaw's eyes sparkled, and at that moment the shop-bell tinkledand a lively whistle sounded. She rose and went into the shop, and Mr.Wright settled back in his chair and scowled darkly as he saw theintruder.

"Good evening," said the latter. "I want a sixpenny smoke for twopence,please. How are we this evening? Sitting up and taking nourishment?"

Miss Bradshaw told him to behave himself.

"Always do," said the young man. "That's why I can never get anybody toplay with. I had such an awful dream about you last night that Icouldn't rest till I saw you. Awful it was."

"What was it?" inquired Miss Bradshaw.

"Dreamt you were married," said Mr. Hills, smiling at her.

Miss Bradshaw tossed her head. "Who to, pray?" she inquired.

"Me," said Mr. Hills, simply. "I woke up in a cold perspiration.Halloa! is that Georgie in there? How are you, George? Better?"

"I'm all right," said Mr. Wright, with dignity, as the other hooked thedoor open with his stick and nodded at him.

"Well, why don't you look it?" demanded the lively Mr. Hills. "Have yougot your feet wet, or what?"

"Oh, be quiet," said Miss Bradshaw, smiling at him.

"Right-o," said Mr. Hills, dropping into a chair by the counter andcaressing his moustache. "But you wouldn't speak to me like that if youknew what a terrible day I've had."

"What have you been doing?" asked the girl.

"Working," said the other, with a huge sigh. "Where's the millionaire?I came round on purpose to have a look at him."

"Him and mother have gone to the Empire?" said Miss Bradshaw.

Mr. Hills gave three long, penetrating whistles, and then, placing hiscigar with great care on the counter, hid his face in a hugehandkerchief. Miss Bradshaw, glanced from him to the frowning Mr.Wright, and then, entering the parlour, closed the door with a bang. Mr.Hills took the hint, and with a somewhat thoughtful grin departed.

He came in next evening for another cigar, and heard all that there wasto hear about the Empire. Mrs. Bradshaw would have treated him butcoldly, but the innocent Mr. Kemp, charmed by his manner, paid him greatattention.

"He's just like what I was at his age," he said. "Lively."

"I'm not a patch on you," said Mr. Hills, edging his way by slow degreesinto the parlour. "I don't take young ladies to the Empire. Were youtelling me you came over here to get married, or did I dream it?"

"'Ark at him," said the blushing Mr. Kemp, as Mrs. Bradshaw shook herhead at the offender and told him to behave himself.

"He's a man any woman might be happy with," said Mr. Hills. "He neverknows how much there is in his trousers-pocket. Fancy sewing on buttonsfor a man like that. Gold-mining ain't in it."

Mrs. Bradshaw shook her head at him again, and Mr. Hills, afterapologizing to her for revealing her innermost thoughts before the mostguileless of men, began to question Mr. Kemp as to the prospects of abright and energetic young man, with a distaste for work, in New Zealand.The audience listened with keen attention to the replies, the onlydisturbing factor being a cough of Mr. Wright's, which became more andmore troublesome as the evening wore on. By the time uncle and nephewrose to depart the latter was so hoarse that he could scarcely speak.

"Why didn't you tell 'em you had got a letter calling you home, as I toldyou?" he vociferated, as soon as they were clear of the shop.

"I--I forgot it," said the old man.

"Forgot it!" repeated the incensed Mr. Wright.

"What did you think I was coughing like that for--fun?"

"I forgot it," said the old man, doggedly. "Besides, if you take myadvice, you'd better let me stay a little longer to make sure of things."

Mr. Wright laughed disagreeably. "I dare say," he said; "but I ammanaging this affair, not you. Now, you go round to-morrow afternoon andtell them you're off. D'ye hear? D'ye think I'm made of money? Andwhat do you mean by making such a fuss of that fool, Charlie Hills? Youknow he is after Bella."

He walked the rest of the way home in indignant silence, and, aftergiving minute instructions to Mr. Kemp next morning at breakfast, wentoff to work in a more cheerful frame of mind. Mr. Kemp was out when hereturned, and after making his toilet he followed him to Mrs. Bradshaw's.

To his annoyance, he found Mr. Hills there again; and, moreover, it soonbecame clear to him that Mr. Kemp had said nothing about his approachingdeparture. Coughs and scowls passed unheeded, and at last in ahesitating voice, he broached the subject himself. There was a generalchorus of lamentation.

"I hadn't got the heart to tell you," said Mr. Kemp. "I don't know whenI've been so happy."

"But you haven't got to go back immediate," said Mrs. Bradshaw.

"To-morrow," said Mr. Wright, before the old man could reply."Business."

"Must you go," said Mrs. Bradshaw.

Mr. Kemp smiled feebly. "I suppose I ought to," he replied, in ahesitating voice.

"Take my tip and give yourself a bit of a holiday before you go back,"urged Mr. Hills.

"Just for a few days," pleaded Bella.

"To please us," said Mrs. Bradshaw. "Think 'ow George'll miss you."

"Lay hold of him and don't let him go," said Mr. Hills.

He took Mr. Kemp round the waist, and the laughing Bella and her mothereach secured an arm. An appeal to Mr. Wright to secure his legs passedunheeded.

"We don't let you go till you promise," said Mrs. Bradshaw.

Mr. Kemp smiled and shook his head. "Promise?" said Bella.

"Well, well," said Mr. Kemp; "p'r'aps--"

"He must go back," shouted the alarmed Mr. Wright.

"Let him speak for himself," exclaimed Bella, indignantly.

"Just another week then," said Mr. Kemp. "It's no good having money if Ican't please myself."

"A week!" shouted Mr. Wright, almost beside himself with rage and dismay."A week! Another week! Why, you told me----"

"Oh, don't listen to him," said Mrs. Bradshaw. "Croaker! It's his ownbusiness, ain't it? And he knows best, don't he? What's it got to dowith you?"

She patted Mr. Kemp's hand; Mr. Kemp patted back, and with his disengagedhand helped himself to a glass of beer--the fourth--and beamed in afriendly fashion upon the company.

"George!" he said, suddenly.

"Yes," said Mr. Wright, in a harsh voice.

"Did you think to bring my pocket-book along with you?"

"No," said Mr. Wright, sharply; "I didn't."

"Tt-tt," said the old man, with a gesture of annoyance. "Well, lend me acouple of pounds, then, or else run back and fetch my pocket-book," headded, with a sly grin.

Mr. Wright's face worked with impotent fury. "What--what--do you--wantit for?" he gasped.

Mrs. Bradshaw's "Well! Well!" seemed to sum up the general feeling; Mr.Kemp, shaking his head, eyed him with gentle reproach.

"Me and Mrs. Bradshaw are going to gave another evening out," he said,quietly. "I've only got a few more days, and I must make hay while thesun shines."

To Mr. Wright the room se

emed to revolve slowly on its axis, but,regaining his self-possession by a supreme effort, he took out his purseand produced the amount. Mrs. Bradshaw, after a few feminineprotestations, went upstairs to put her bonnet on.

"And you can go and fetch a hansom-cab, George, while she's a-doing ofit," said Mr. Kemp. "Pick out a good 'orse--spotted-grey, if you can."

Mr. Wright arose and, departing with a suddenness that was almoststartling, exploded harmlessly in front of the barber's, next door butone. Then with lagging steps he went in search of the shabbiest cab andoldest horse he could find.

"Thankee, my boy," said Mr. Kemp, bluffly, as he helped Mrs. Bradshaw inand stood with his foot on the step. "By the way, you had better go backand lock my pocket-book up. I left it on the washstand, and there's bestpart of a thousand pounds in it. You can take fifty for yourself to buysmokes with."

There was a murmur of admiration, and Mr. Wright, with a frantic attemptto keep up appearances, tried to thank him, but in vain. Long after thecab had rolled away he stood on the pavement trying to think out aposition which was rapidly becoming unendurable. Still keeping upappearances, he had to pretend to go home to look after the pocket-book,leaving the jubilant Mr. Hills to improve the shining hour with MissBradshaw.

Mr. Kemp, returning home at midnight--in a cab--found the young manwaiting up for him, and, taking a seat on the edge of the table, listenedunmoved to a word-picture of himself which seemed interminable. He wasonly moved to speech when Mr. Wright described him as a white-whiskeredjezebel who was a disgrace to his sex, and then merely in the interestsof natural science.

"Don't you worry," he said, as the other paused from exhaustion. "Itwon't be for long now."

"Long?" said Mr. Wright, panting. "First thing to-morrow morning youhave a telegram calling you back--a telegram that must be minded. D'yesee?"

"No, I don't," said Mr. Kemp, plainly. "I'm not going back, never nomore--never! I'm going to stop here and court Mrs. Bradshaw."

Mr. Wright fought for breath. "You--you can't!" he gasped.

"I'm going to have a try," said the old man. "I'm sick of going to sea,and it'll be a nice comfortable home for my old age. You marry Bella,and I'll marry her mother. Happy family!"

Mr. Wright, trembling with rage, sat down to recover, and, regaining hiscomposure after a time, pointed out almost calmly the variousdifficulties in the way.

"I've thought it all out," said Mr. Kemp, nodding. "She mustn't know I'mnot rich till after we're married; then I 'ave a letter from New Zealandsaying I've lost all my money. It's just as easy to have that letter asthe one you spoke of."

"And I'm to find you money to play the rich uncle with till you'remarried, I suppose," said Mr. Wright, in a grating voice, "and then loseBella when Mrs. Bradshaw finds you've lost your money?"

Mr. Kemp scratched his ear. "That's your lookout," he said, at last.

"Now, look here," said Mr. Wright, with great determination. "Either yougo and tell them that you've been telegraphed for--cabled is the properword--or I tell them the truth."

"That'll settle you then," said Mr. Kemp.

"No more than the other would," retorted the young man, "and it'll comecheaper. One thing I'll take my oath of, and that is I won't give youanother farthing; but if you do as I tell you I'll give you a quid forluck. Now, think it over."

Mr. Kemp thought it over, and after a vain attempt to raise the promisedreward to five pounds, finally compounded for two, and went off to bedafter a few stormy words on selfishness and ingratitude. He declined tospeak to his host at breakfast next morning, and accompanied him in theevening with the air of a martyr going to the stake. He listened instony silence to the young man's instructions, and only spoke when thelatter refused to pay the two pounds in advance.

The news, communicated in halting accents by Mr. Kemp, was received withflattering dismay. Mrs. Bradshaw refused to believe her ears, and it wasonly after the information had been repeated and confirmed by Mr. Wrightthat she understood.

"I must go," said Mr. Kemp. "I've spent over eleven pounds cablingto-day; but it's all no good."

"But you're coming back?" said Mr. Hills.

"O' course I am," was the reply. "George is the only relation I've got,and I've got to look after him, I suppose. After all, blood is thickerthan water."

"Hear, hear!" said Mrs. Bradshaw, piously.

"And there's you and Bella," continued Mr. Kemp; "two of the best thatever breathed."

The ladies looked down.

"And Charlie Hills; I don't know--I don't know _when_ I've took such afancy to anybody as I have to 'im. If I was a young gal--a single younggal--he's--the other half," he said, slowly, as he paused--"just the one Ishould fancy. He's a good-'arted, good-looking----"

"Draw it mild," interrupted the blushing Mr. Hills as Mr. Wright bestoweda ferocious glance upon the speaker.

"Clever, lively young fellow," concluded Mr. Kemp. "George!"

"Yes," said Mr. Wright.

"I'm going now. I've got to catch the train for Southampton, but I don'twant you to come with me. I prefer to be alone. You stay here and cheerthem up. Oh, and before I forget it, lend me a couple o' pounds out o'that fifty I gave you last night. I've given all my small change away."

He looked up and met Mr. Wright's eye; the latter, too affected to speak,took out the money and passed it over.

"We never know what may happen to us," said the old man, solemnly, as herose and buttoned his coat. "I'm an old man and I like to have thingsship-shape. I've spent nearly the whole day with my lawyer, and ifanything 'appens to my old carcass it won't make any difference. I haveleft half my money to George; half of all I have is to be his."

In the midst of an awed silence he went round and shook hands.

"The other half," with his hand on the door--"the other half and my bestgold watch and chain I have left to my dear young pal, Charlie Hills.Good-bye, Georgie!"

"MANNERS MAKYTH MAN"

The night-watchman appeared to be out of sorts. His movements were evenslower than usual, and, when he sat, the soap-box seemed to be unable togive satisfaction. His face bore an expression of deep melancholy, but asmouldering gleam in his eye betokened feelings deeply moved.

"Play-acting I don't hold with," he burst out, with sudden ferocity."Never did. I don't say I ain't been to a theayter once or twice in mylife, but I always come away with the idea that anybody could act if theyliked to try. It's a kid's game, a silly kid's game, dressing up andpretending to be somebody else."

He cut off a piece of tobacco and, stowing it in his left cheek, satchewing, with his lack-lustre eyes fixed on the wharves across the river.The offensive antics of a lighterman in mid-stream, who nearly felloverboard in his efforts to attract his attention, he ignored.

"I might ha' known it, too," he said, after a long silence. "If I'd onlystopped to think, instead o' being in such a hurry to do good to others,I should ha' been all right, and the pack o' monkey-faced swabs on the_Lizzie and Annie_ wot calls themselves sailor-men would 'ave had to 'avegot something else to laugh about. They've told it in every pub for 'arfa mile round, and last night, when I went into the Town of Margate to geta drink, three chaps climbed over the partition to 'ave a look at me.

"It all began with young Ted Sawyer, the mate o' the _Lizzie and Annie_.He calls himself a mate, but if it wasn't for 'aving the skipper for abrother-in-law 'e'd be called something else, very quick. Two or threetimes we've 'ad words over one thing and another, and the last time Icalled 'im something that I can see now was a mistake. It was one o'these 'ere clever things that a man don't forget, let alone a lop-sidedmonkey like 'im.

"That was when they was up time afore last, and when they made fast 'erelast week I could see as he 'adn't forgotten it. For one thing hepretended not to see me, and, arter I 'ad told him wot I'd do to him if'e ran into me agin, he said 'e thought I was a sack o' potatoes taking aairing on a pair of legs wot somebody 'ad throwed away. Nasty tongue'e's

got; not clever, but nasty.

"Arter that I took no notice of 'im, and, o' course, that annoyed 'immore than anything. All I could do I done, and 'e was ringing thegate-bell that night from five minutes to twelve till ha'-past afore Iheard it. Many a night-watchman gets a name for going to sleep when'e's only getting a bit of 'is own back.

"We stood there talking for over 'arf-an-hour arter I 'ad let'im in.Leastways, he did. And whenever I see as he was getting tired I justsaid, 'H'sh!' and 'e'd start agin as fresh as ever. He tumbled to it atlast, and went aboard shaking 'is little fist at me and telling me wothe'd do to me if it wasn't for the lor.

"I kept by the gate as soon as I came on dooty next evening, just to give'im a little smile as 'e went out. There is nothing more aggravatingthan a smile when it is properly done; but there was no signs o' my lord,and, arter practising it on a carman by mistake, I 'ad to go inside for abit and wait till he 'ad gorn.

"The coast was clear by the time I went back, and I 'ad just steppedoutside with my back up agin the gate-post to 'ave a pipe, when I see aboy coming along with a bag. Good-looking lad of about fifteen 'e was,nicely dressed in a serge suit, and he no sooner gets up to me than 'eputs down the bag and looks up at me with a timid sort o' little smile.

"'Good evening, cap'n,' he ses.

"He wasn't the fust that has made that mistake; older people than 'imhave done it.

"'Good evening, my lad,' I ses.

"'I s'pose,' he ses, in a trembling voice, 'I suppose you ain't lookingout for a cabin-boy, sir?'

"'Cabin-boy?' I ses. 'No, I ain't.'

"'I've run away from 'ome to go to sea,' he ses, and I'm afraid of beingpursued. Can I come inside?'

"Afore I could say 'No' he 'ad come, bag and all; and afore I could sayanything else he 'ad nipped into the office and stood there with his 'andon his chest panting.

"'I know I can trust you,' he ses; 'I can see it by your face."

"'Wot 'ave you run away from 'ome for?' I ses. 'Have they beenill-treating of you?'

"'Ill-treating me?' he ses, with a laugh. 'Not much. Why, I expect myfather is running about all over the place offering rewards for me. Hewouldn't lose me for a thousand pounds.'

"I pricked up my ears at that; I don't deny it. Anybody would. Besides,I knew it would be doing him a kindness to hand 'im back to 'is father.And then I did a bit o' thinking to see 'ow it was to be done.

"'Sit down,' I ses, putting three or four ledgers on the floor behind oneof the desks. 'Sit down, and let's talk it over.'

"We talked away for ever so long, but, do all I would, I couldn'tpersuade 'im. His 'ead was stuffed full of coral islands and smugglersand pirates and foreign ports. He said 'e wanted to see the world, andflying-fish.

"'I love the blue billers,' he ses; 'the heaving blue billers is wot Iwant.'

"I tried to explain to 'im who would be doing the heaving, but 'ewouldn't listen to me. He sat on them ledgers like a little woodenimage, looking up at me and shaking his 'ead, and when I told 'im ofstorms and shipwrecks he just smacked 'is lips and his blue eyes shonewith joy. Arter a time I saw it was no good trying to persuade 'im, andI pretended to give way.

"'I think I can get you a ship with a friend o' mine,' I ses; 'but, mind,I've got to relieve your pore father's mind--I must let 'im know wot'sbecome of you.'

"'Not before I've sailed,' he ses, very quick.

"'Certingly not,' I ses. 'But you must give me 'is name and address,and, arter the Blue Shark--that's the name of your ship--is clear of theland, I'll send 'im a letter with no name to it, saying where you avegorn.'

"He didn't seem to like it at fust, and said 'e would write 'imself, butarter I 'ad pointed out that 'e might forget and that I was responsible,'e gave way and told me that 'is father was named Mr. Watson, and he kepta big draper's shop in the Commercial Road.

"We talked a bit arter that, just to stop 'is suspicions, and then I told'im to stay where 'e was on the floor, out of sight of the window, whileI went to see my friend the captain.

"I stood outside for a moment trying to make up my mind wot to do.O'course, I 'ad no business, strictly speaking, to leave the wharf, but,on the other 'and, there was a father's 'art to relieve. I edged alongbit by bit while I was thinking, and then, arter looking back once ortwice to make sure that the boy wasn't watching me, I set off for theCommercial Road as hard as I could go.

"I'm not so young as I was. It was a warm evening, and I 'adn't got evena bus fare on me. I 'ad to walk all the way, and, by the time I gotthere, I was 'arf melted. It was a tidy-sized shop, with three or fournice-looking gals behind the counter, and things like babies' high chairsfor the customers to sit onlong in the leg and ridikerlously small in theseat. I went up to one of the gals and told Per I wanted to see Mr.Watson.

"'On private business,' I ses. 'Very important.'

"She looked at me for a moment, and then she went away and fetched atall, bald-headed man with grey side-whiskers and a large nose.

"'Wot d'you want?" he ses, coming up to me.

I want a word with you in private,' I ses.

"'This is private enough for me,' he ses. 'Say wot you 'ave to say, andbe quick about it.'

"I drawed myself up a bit and looked at him. 'P'r'aps you ain't missed'im yet,' I ses.

"'Missed 'im?' he ses, with a growl. 'Missed who?'

"'Your-son. Your blue-eyed son,' I ses, looking 'im straight in the eye.

"'Look here!' he ses, spluttering. 'You be off. 'Ow dare you come herewith your games? Wot d'ye mean by it?'

"'I mean,' I ses, getting a bit out o' temper, 'that your boy has runaway to go to sea, and I've come to take you to 'im.'

"He seemed so upset that I thought 'e was going to 'ave a fit at fust,and it seemed only natural, too. Then I see that the best-looking girland another was having a fit, although trying 'ard not to.

"'If you don't get out o' my shop,' he ses at last, 'I'll 'ave you lockedup.'

"'Very good!' I ses, in a quiet way. 'Very good; but, mark my words,if he's drownded you'll never forgive yourself as long as you live forletting your temper get the better of you--you'll never know a goodnight's rest agin. Besides, wot about 'is mother?'

"One o' them silly gals went off agin just like a damp firework, and Mr.Watson, arter nearly choking 'imself with temper, shoved me out o' theway and marched out o' the shop. I didn't know wot to make of 'im atfust, and then one o' the gals told me that 'e was a bachelor and 'adn'tgot no son, and that somebody 'ad been taking advantage of what shecalled my innercence to pull my leg.

"'You toddle off 'ome,' she ses, 'before Mr. Watson comes back.'

"'It's a shame to let 'im come out alone,' ses one o' the other gals.'Where do you live, gran'pa?'

"I see then that I 'ad been done, and I was just walking out o' the shop,pretending to be deaf, when Mr. Watson come back with a silly youngpoliceman wot asked me wot I meant by it. He told me to get off 'omequick, and actually put his 'and on my shoulder, but it 'ud take morethan a thing like that to push me, and, arter trying his 'ardest, hecould only rock me a bit.

"I went at last because I wanted to see that boy agin, and the youngpoliceman follered me quite a long way, shaking his silly 'ead at me andtelling me to be careful.

"I got a ride part o' the way from Commercial Road to Aldgate by gettingon the wrong bus, but it wasn't much good, and I was quite tired by thetime I got back to the wharf. I waited outside for a minute or two toget my wind back agin, and then I went in-boiling.

"You might ha' knocked me down with a feather, as the saying is, and Ijust stood inside the office speechless. The boy 'ad disappeared andsitting on the floor where I 'ad left 'im was a very nice-looking gal ofabout eighteen, with short 'air, and a white blouse.

"'Good evening, sir,' she ses, jumping up and giving me a pretty littlefrightened look. 'I'm so sorry that my brother has been deceiving you.He's a bad, wicked, ungrateful boy. The idea of telling you that Mr.Watson was 'is father! Have you been

there? I do 'ope you're nottired.'

"'Where is he?' I ses.

"'He's gorn,' she ses, shaking her 'ead. 'I begged and prayed of 'im tostop, but 'e wouldn't. He said 'e thought you might be offended with'im. "Give my love to old Roley-Poley, and tell him I don't trust 'im,"he ses.'

"She stood there looking so scared that I didn't know wot to say. By andby she took out 'er little pocket-'ankercher and began to cry--

"'Oh, get 'im back,' she ses. 'Don't let it be said I follered 'im 'ereall the way for nothing. Have another try. For my sake!'

"''Ow can I get 'im back when I don't know where he's gorn?' I ses.

"'He-he's gorn to 'is godfather,' she ses, dabbing her eyes. 'I promised'im not to tell anybody; but I don't know wot to do for the best.'

"'Well, p'r'aps his godfather will 'old on to 'im,' I ses.

"'He won't tell 'im anything about going to sea,' she ses, shaking 'erlittle head. 'He's just gorn to try and bo--bo-borrow some money to goaway with.'

"She bust out sobbing, and it was all I could do to get the godfather'saddress out of 'er. When I think of the trouble I took to get it I comeover quite faint. At last she told me, between 'er sobs, that 'is namewas Mr. Kiddem, and that he lived at 27, Bridge Street.

"'He's one o' the kindest-'arted and most generous men that ever lived,'she ses; 'that's why my brother Harry 'as gone to 'im. And you needn'tmind taking anything 'e likes to give you; he's rolling in money.'

"I took it a bit easier going to Bridge Street, but the evening seemed'otter than ever, and by the time I got to the 'ouse I was pretty neardone up. A nice, tidy-looking woman opened the door, but she was a' moststone deaf, and I 'ad to shout the name pretty near a dozen times aforeshe 'eard it.

"'He don't live 'ere,' she ses.

"''As he moved?' I ses. 'Or wot?'

"She shook her 'cad, and, arter telling me to wait, went in and fetchedher 'usband.

"'Never 'eard of him,' he ses, 'and we've been 'ere seventeen years. Areyou sure it was twenty-seven?'

"'Sartain,' I ses.

"'Well, he don't live 'ere,' he ses. 'Why not try thirty-seven andforty-seven?'

"I tried'em: thirty-seven was empty, and a pasty-faced chap atforty-seven nearly made 'imself ill over the name of 'Kiddem.' It'adn't struck me before, but it's a hard matter to deceive me, and allin a flash it come over me that I 'ad been done agin, and that the galwas as bad as 'er brother.

"I was so done up I could 'ardly crawl back, and my 'ead was all in amaze. Three or four times I stopped and tried to think, but couldn't,but at last I got back and dragged myself into the office.

"As I 'arf expected, it was empty. There was no sign of either the galor the boy; and I dropped into a chair and tried to think wot it allmeant. Then, 'appening to look out of the winder, I see somebody runningup and down the jetty.

"I couldn't see plain owing to the things in the way, but as soon as Igot outside and saw who it was I nearly dropped. It was the boy, and hewas running up and down wringing his 'ands and crying like a wild thing,and, instead o' running away as soon as 'e saw me, he rushed right up tome and threw 'is grubby little paws round my neck.

"'Save her!' 'e ses. 'Save 'er! Help! Help!'

"'Look 'ere,' I ses, shoving 'im off.

"'She fell overboard,' he ses, dancing about. 'Oh, my pore sister!Quick! Quick! I can't swim!'

"He ran to the side and pointed at the water, which was just about at'arf-tide. Then 'e caught 'old of me agin.

"'Make 'aste,' he ses, giving me a shove behind. 'Jump in. Wot are youwaiting for?'

"I stood there for a moment 'arf dazed, looking down at the water. ThenI pulled down a life-belt from the wall 'ere and threw it in, and, arteranother moment's thought, ran back to the _Lizzie and Annie,_ wot was inthe inside berth, and gave them a hail. I've always 'ad a good voice,and in a flash the skipper and Ted Sawyer came tumbling up out of thecabin and the 'ands out of the fo'c'sle.

"'Gal overboard!' I ses, shouting.

"The skipper just asked where, and then 'im and the mate and a couple of'ands tumbled into their boat and pulled under the jetty for all they wasworth. Me and the boy ran back and stood with the others, watching.

"'Point out the exact spot,' ses the skipper.

"The boy pointed, and the skipper stood up in the boat and felt roundwith a boat-hook. Twice 'e said he thought 'e touched something, but itturned out as 'e was mistaken. His face got longer and longer and 'eshook his 'ead, and said he was afraid it was no good.

"'Don't stand cryin' 'ere,' he ses to the boy, kindly. 'Jem, run roundfor the Thames police, and get them and the drags. Take the boy withyou. It'll occupy 'is mind.'

"He 'ad another go with the boat-hook arter they 'ad gone; then 'e gaveit up, and sat in the boat waiting.

"'This'll be a bad job for you, watchman,' he ses, shaking his 'ead.'Where was you when it 'appened?'

"'He's been missing all the evening,' ses the cook, wot was standingbeside me. 'If he'd been doing 'is dooty, the pore gal wouldn't 'avebeen drownded. Wot was she doing on the wharf?'

"'Skylarkin', I s'pose,' ses the mate. 'It's a wonder there ain't moredrownded. Wot can you expect when the watchman is sitting in a pub allthe evening?'

"The cook said I ought to be 'ung, and a young ordinary seaman wot wasstanding beside 'im said he would sooner I was boiled. I believe they'ad words about it, but I was feeling too upset to take much notice.

"'Looking miserable won't bring 'er back to life agin,' ses the skipper,looking up at me and shaking his 'ead. 'You'd better go down to my cabinand get yourself a drop o' whisky; there's a bottle on the table. You'llwant all your wits about you when the police come. And wotever you dodon't say nothing to criminate yourself.'

"'We'll do the criminating for 'im all right,' ses the cook.

"'If I was the pore gal I'd haunt 'im,' ses the ordinary seaman; 'everynight of 'is life I'd stand afore 'im dripping with water and moaning.'

"'P'r'aps she will,' ses the cook; 'let's 'ope so, at any rate.'

"I didn't answer 'em; I was too dead-beat. Besides which, I've got a'orror of ghosts, and the idea of being on the wharf alone of a nightarter such a thing was a'most too much for me. I went on board the_Lizzie and Annie,_ and down in the cabin I found a bottle o' whisky, asthe skipper 'ad said. I sat down on the locker and 'ad a glass, and thenI sat worrying and wondering wot was to be the end of it all.

"The whisky warmed me up a bit, and I 'ad just taken up the bottle to'elp myself agin when I 'eard a faint sort o' sound in the skipper'sstate-room. I put the bottle down and listened, but everything seemeddeathly still. I took it up agin, and 'ad just poured out a drop o'whisky when I distinctly 'eard a hissing noise and then a little moan.

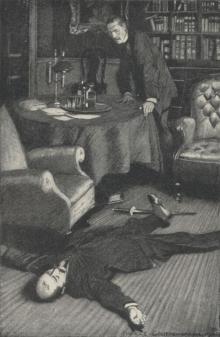

"For a moment I sat turned to stone. Then I put the bottle down quiet,and 'ad just got up to go when the door of the state-room opened, and Isaw the drownded gal, with 'er little face and hair all wet and dripping,standing before me.

"Ted Sawyer 'as been telling everybody that I came up the companion-waylike a fog-horn that 'ad lost its ma; I wonder how he'd 'ave come up ifhe'd 'ad the evening I had 'ad?

"They were all on the jetty as I got there and tumbled into the skipper'sarms, and all asking at once wot was the matter. When I got my breathback a bit and told 'em, they laughed. All except the cook, and 'e saidit was only wot I might expect. Then, like a man in a dream, I see thegal come out of the companion and walk slowly to the side.

"'Look!' I ses. 'Look. There she is!'

"'You're dreaming,' ses the skipper, 'there's nothing there.'

"They all said the same, even when the gal stepped on to the side andclimbed on to the wharf. She came along towards me with 'er arms heldclose to 'er sides, and making the most 'orrible faces at me, and it tookfive of'em all their time to 'old me. The wharf and everything seemed tome to spin round and round. Then she came straight up to me and pattedme on the cheek.

"'Pore old gentleman,' she

ses. 'Wot a shame it is, Ted! It's too bad.'

"They let go o' me then, and stamped up and down the jetty laughing fitto kill themselves. If they 'ad only known wot a exhibition they wasmaking of themselves, and 'ow I pitied them, they wouldn't ha' done it.And by and by Ted wiped his eyes and put his arm round the gal's waistand ses--

"'This is my intended, Miss Florrie Price,' he ses. 'Ain't she a littlewonder? Wot d'ye think of 'er?'

"'I'll keep my own opinion,' I ses. 'I ain't got nothing to say againstgals, but if I only lay my hands on that young brother of 'ers'

"They went off agin then, worse than ever; and at last the cook came andput 'is skinny arm round my neck and started spluttering in my ear. Ishoved 'im off hard, because I see it all then; and I should ha' seen itafore only I didn't 'ave time to think. I don't bear no malice, and allI can say is that I don't wish 'er any harder punishment than to bemarried to Ted Sawyer."

_preview.jpg) Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection)

Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection) The Monkey's Paw

The Monkey's Paw Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II

Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II Odd Craft, Complete

Odd Craft, Complete The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection

The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection Deep Waters, the Entire Collection

Deep Waters, the Entire Collection Three at Table

Three at Table Light Freights

Light Freights Night Watches

Night Watches The Three Sisters

The Three Sisters Ship's Company, the Entire Collection

Ship's Company, the Entire Collection His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts

His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts Fine Feathers

Fine Feathers My Man Sandy

My Man Sandy Self-Help

Self-Help Captains All and Others

Captains All and Others Back to Back

Back to Back More Cargoes

More Cargoes Believe You Me!

Believe You Me! Keeping Up Appearances

Keeping Up Appearances The Statesmen Snowbound

The Statesmen Snowbound An Adulteration Act

An Adulteration Act The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches

The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches Husbandry

Husbandry Love and the Ironmonger

Love and the Ironmonger The Old Man's Bag

The Old Man's Bag Dirty Work

Dirty Work Easy Money

Easy Money The Lady of the Barge

The Lady of the Barge Bedridden and the Winter Offensive

Bedridden and the Winter Offensive Odd Charges

Odd Charges Friends in Need

Friends in Need Watch-Dogs

Watch-Dogs Cupboard Love

Cupboard Love Captains All

Captains All A Spirit of Avarice

A Spirit of Avarice The Nest Egg

The Nest Egg The Guardian Angel

The Guardian Angel The Convert

The Convert Captain Rogers

Captain Rogers Breaking a Spell

Breaking a Spell Striking Hard

Striking Hard The Bequest

The Bequest Shareholders

Shareholders The Weaker Vessel

The Weaker Vessel John Henry Smith

John Henry Smith Four Pigeons

Four Pigeons Made to Measure

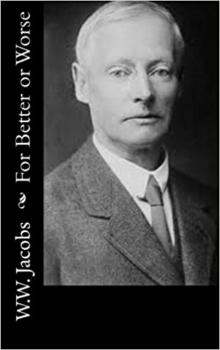

Made to Measure For Better or Worse

For Better or Worse Fairy Gold

Fairy Gold Family Cares

Family Cares Good Intentions

Good Intentions Prize Money

Prize Money The Temptation of Samuel Burge

The Temptation of Samuel Burge The Madness of Mr. Lister

The Madness of Mr. Lister The Constable's Move

The Constable's Move Paying Off

Paying Off Double Dealing

Double Dealing A Mixed Proposal

A Mixed Proposal Bill's Paper Chase

Bill's Paper Chase The Changing Numbers

The Changing Numbers Over the Side

Over the Side Lawyer Quince

Lawyer Quince The White Cat

The White Cat Admiral Peters

Admiral Peters The Third String

The Third String The Vigil

The Vigil Bill's Lapse

Bill's Lapse His Other Self

His Other Self Matrimonial Openings

Matrimonial Openings The Substitute

The Substitute Deserted

Deserted Dual Control

Dual Control Homeward Bound

Homeward Bound Sam's Ghost

Sam's Ghost The Unknown

The Unknown Stepping Backwards

Stepping Backwards Sentence Deferred

Sentence Deferred The Persecution of Bob Pretty

The Persecution of Bob Pretty Skilled Assistance

Skilled Assistance A Golden Venture

A Golden Venture Establishing Relations

Establishing Relations A Tiger's Skin

A Tiger's Skin Bob's Redemption

Bob's Redemption Manners Makyth Man

Manners Makyth Man The Head of the Family

The Head of the Family The Understudy

The Understudy Odd Man Out

Odd Man Out Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary

Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence Blundell's Improvement

Blundell's Improvement The Toll-House

The Toll-House Dixon's Return

Dixon's Return Keeping Watch

Keeping Watch The Boatswain's Mate

The Boatswain's Mate The Castaway

The Castaway In the Library

In the Library The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre