- Home

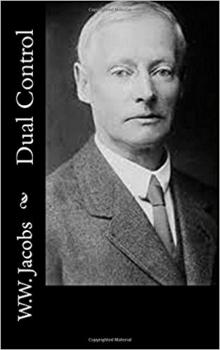

- W. W. Jacobs

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre Page 12

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre Read online

Page 12

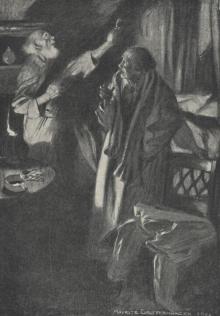

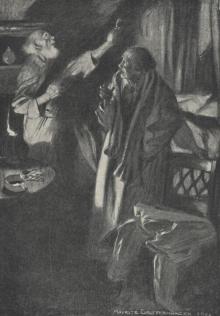

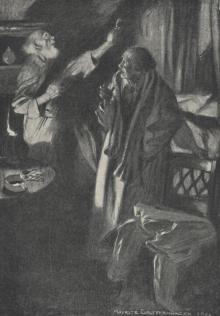

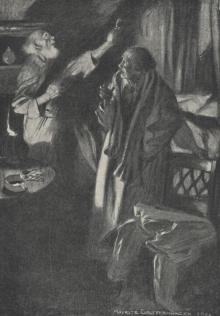

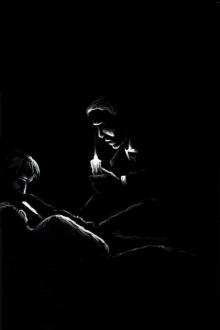

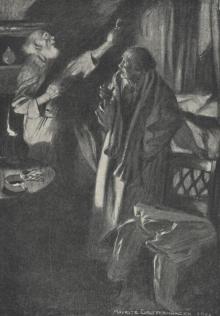

He rose in bed, and with a sudden movement flung the other over on his back. Gunn’s eyes were starting from his head, and he writhed convulsively.

“I thought you were a sharper man, Gunn,” said Rogers, still in the same hot whisper, as he relaxed his grip a little; “you are too simple, you hound! When you first threatened me I resolved to kill you. Then you threatened my daughter. I wish that you had nine lives, that I might take them all. Keep still!”

He gave a half-glance over his shoulder at the silent figure of the nurse, and put his weight on the twisting figure on the bed.

“You drugged the hag, good Gunn,” he continued. “Tomorrow morning, Gunn, they will find you in your room dead, and if one of the scum you brought into my house be charged with the murder, so much the better. When I am well they will go. I am already feeling a little bit stronger, Gunn, as you see, and in a month I hope to be about again.”

He averted his face, and for a time gazed sternly and watchfully at the door. Then he rose slowly to his feet, and taking the dead man in his arms, bore him slowly and carefully to his room, and laid him a huddled heap on the floor. Swiftly and noiselessly he put the dead man’s shoes on and turned his pockets inside out, kicked a rug out of place, and put a guinea on the floor. Then he stole cautiously down stairs and set a small door at the back open. A dog barked frantically, and he hurried back to his room. The nurse still slumbered by the fire.

She awoke in the morning shivering with the cold, and being jealous of her reputation, rekindled the fire, and measuring out the dose which the invalid should have taken, threw it away. On these unconscious preparations for an alibi Captain Rogers gazed through half-closed lids, and then turning his grim face to the wall, waited for the inevitable alarm.

10

The Lost Ship

On a fine spring morning in the early part of the present century, Tetby, a small port on the east coast, was keeping high holiday. Tradesmen left their shops, and labourers their work, and flocked down to join the maritime element collected on the quay.

In the usual way Tetby was a quiet, dull little place, clustering in a tiny heap on one side of the river, and perching in scattered red-tiled cottages on the cliffs of the other.

Now, however, people were grouped upon the stone quay, with its litter of fish-baskets and coils of rope, waiting expectantly, for today the largest ship ever built in Tetby, by Tetby hands, was to start upon her first voyage.

As they waited, discussing past Tetby ships, their builders, their voyages, and their fate, a small piece of white sail showed on the noble barque from her moorings up the river. The groups on the quay grew animated as more sail was set, and in a slow and stately fashion the new ship drew near. As the light breeze took her sails she came faster, sitting the water like a duck, her lofty masts tapering away to the sky as they broke through the white clouds of canvas. She passed within ten fathoms of the quay, and the men cheered and the women held their children up to wave farewell, for she was manned from captain to cabin boy by Tetby men, and bound for the distant southern seas.

Outside the harbour she altered her course somewhat and bent, like a thing of life, to the wind blowing outside. The crew sprang into the rigging and waved their caps, and kissed their grimy hands to receding Tetby. They were answered by rousing cheers from the shore, hoarse and masculine, to drown the lachrymose attempts of the women.

They watched her until their eyes were dim, and she was a mere white triangular speck on the horizon. Then, like a melting snowflake, she vanished into air, and the Tetby folk, some envying the bold mariners, and others thankful that their lives were cast upon the safe and pleasant shore, slowly dispersed to their homes.

Months passed, and the quiet routine of Tetby went on undisturbed. Other craft came into port and, discharging and loading in an easy, comfortable fashion, sailed again. The keel of another ship was being laid in the shipyard, and slowly the time came round when the return of Tetby’s Pride, for so she was named, might be reasonably looked for.

It was feared that she might arrive in the night—the cold and cheerless night, when wife and child were abed, and even if roused to go down on to the quay would see no more of her than her sidelights staining the water, and her dark form stealing cautiously up the river. They would have her come by day. To see her first on that horizon, into which she had dipped and vanished. To see her come closer and closer, the good stout ship seasoned by southern seas and southern suns, with the crew crowding the sides to gaze at Tetby, and see how the children had grown.

But she came not. Day after day the watchers waited for her in vain. It was whispered at length that she was overdue, and later on, but only by those who had neither kith nor kin aboard of her, that she was missing.

Long after all hope had gone wives and mothers, after the manner of their kind, watched and waited on the cheerless quay. One by one they stayed away, and forgot the dead to attend to the living. Babes grew into sturdy, ruddy-faced boys and girls, boys and girls into young men and women, but no news of the missing ship, no word from the missing men. Slowly year succeeded year, and the lost ship became a legend. The man who had built her was old and grey, and time had smoothed away the sorrows of the bereaved.

It was on a dark, blustering September night that an old woman sat by her fire knitting. The fire was low, for it was more for the sake of company than warmth, and it formed an agreeable contrast to the wind which whistled round the house, bearing on its wings the sound of the waves as they came crashing ashore.

“God help those at sea to-night,” said the old woman devoutly, as a stronger gust than usual shook the house.

She put her knitting in her lap and clasped her hands, and at that moment the cottage door opened. The lamp flared and smoked up the chimney with the draught, and then went out. As the old woman rose from her seat the door closed.

“Who’s there?” she cried nervously.

Her eyes were dim and the darkness sudden, but she fancied she saw something standing by the door, and snatching a spill from the mantelpiece she thrust it into the fire, and relit the lamp.

A man stood on the threshold, a man of middle age, with white drawn face and scrubby beard. His clothes were in rags, his hair unkempt, and his light grey eyes sunken and tired.

The old woman looked at him, and waited for him to speak. When he did so he took a step towards her, and said—

“Mother!”

With a great cry she threw herself upon his neck and strained him to her withered bosom, and kissed him. She could not believe her eyes, her senses, but clasped him convulsively, and bade him speak again, and wept, and thanked God, and laughed all in a breath.

Then she remembered herself, and led him tottering to the old Windsor chair, thrust him in it, and quivering with excitement took food and drink from the cupboard and placed before him. He ate hungrily, the old woman watching him, and standing by his side to keep his glass filled with the homebrewed beer. At times he would have spoken, but she motioned him to silence and bade him eat, the tears coursing down her aged checks as she looked at his white famished face.

At length he laid down his knife and fork, and drinking off the ale, intimated that he had finished.

“My boy, my boy,” said the old woman in a broken voice, “I thought you had gone down with Tetby’s Pride long years ago.

He shook his head heavily.

“The captain and crew, and the good ship,” asked his mother. “Where are they?”

“Captain—and—crew,” said the son, in a strange hesitating fashion; “it is a long story—the ale has made me heavy. They are—”

He left off abruptly and closed his eyes.

“Where are they?” asked his mother. “What happened?”

He opened his eyes slowly.

“I—am—tired—dead tired. I have not—slept. I’ll tell—you—morning.”

He nodded again, and the old woman shook him gently.

“Go to bed then. Your old bed, Jem. It’s

as you left it, and it’s made and the sheets aired. It’s been ready for you ever since.”

He rose to his feet, and stood swaying to and fro. His mother opened a door in the wall, and taking the lamp lighted him up the steep wooden staircase to the room he knew so well. Then he took her in his arms in a feeble hug, and kissing her on the forehead sat down wearily on the bed.

The old woman returned to her kitchen, and falling upon her knees remained for some time in a state of grateful, pious ecstasy. When she arose she thought of those other women, and, snatching a shawl from its peg behind the door, ran up the deserted street with her tidings.

In a very short time the town was astir. Like a breath of hope the whisper flew from house to house. Doors closed for the night were thrown open, and wondering children questioned their weeping mothers. Blurred images of husbands and fathers long since given over for dead stood out clear and distinct, smiling with bright faces upon their dear ones.

At the cottage door two or three people had already collected, and others were coming up the street in an unwonted bustle.

They found their way barred by an old woman—a resolute old woman, her face still working with the great joy which had come into her old life, but who refused them admittance until her son had slept. Their thirst for news was uncontrollable, but with a swelling in her throat she realized that her share in Tetby’s Pride was safe.

Women who had waited, and got patient at last after years of waiting, could not endure these additional few hours. Despair was endurable, but suspense! “Ah, God! Was their man alive? What did he look like? Had he aged much?”

“He was so fatigued he could scarce speak,” said she. She had questioned him, but he was unable to reply. Give him but till the dawn, and they should know all.

So they waited, for to go home and sleep was impossible. Occasionally they moved a little way up the street, but never very far, and gathering in small knots excitedly discussed the great event. It came to be understood that the rest of the crew had been cast away on an uninhabited island, it could be nothing else, and would doubtlessly soon be with them; all except one or two perhaps, who were old men when the ship sailed, and had probably died in the meantime. One said this in the hearing of an old woman whose husband, if alive, would be in extreme old age, but she smiled peacefully, albeit her lip trembled, and said she only expected to hear of him, that was all.

The suspense became almost unendurable. “Would this man never awake? Would it never be dawn?” The children were chilled with the wind, but their elders would scarcely have felt an Arctic frost. With growing impatience they waited, glancing at times at two women who held themselves somewhat aloof from the others; two women who had married again, and whose second husbands waited, awkwardly enough, with them.

Slowly the weary windy night wore away, the old woman, deaf to their appeals, still keeping her door fast. The dawn was not yet, though the oft-consulted watches announced it near at hand. It was very close now, and the watchers collected by the door. It was undeniable that things were seen a little more distinctly. One could see better the grey, eager faces of his neighbours.

They knocked upon the door, and the old woman’s eyes filled as she opened it and saw those faces. Unasked and unchid they invaded the cottage and crowded round the door.

“I will go up and fetch him,” said the old woman.

If each could have heard the beating of the others’ hearts, the noise would have been deafening, but as it was there was complete silence, except for some overwrought woman’s sob.

The old woman opened the door leading to the room above, and with the slow, deliberate steps of age ascended the stairs, and those below heard her calling softly to her son.

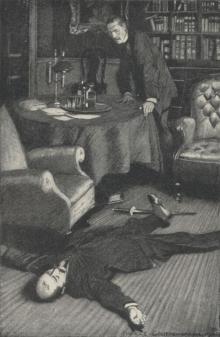

Two or three minutes passed and she was heard descending the stairs again—alone. The smile, the pity, had left her face, and she seemed dazed and strange.

“I cannot wake him,” she said piteously. “He sleeps so sound. He is fatigued. I have shaken him, but he still sleeps.”

As she stopped, and looked appealingly round, the other old woman took her hand, and pressing it led her to a chair. Two of the men sprang quickly up the stairs. They were absent but a short while, and then they came down like men bewildered and distraught. No need to speak. A low wail of utter misery rose from the women, and was caught up and repeated by the crowd outside, for the only man who could have set their hearts at rest had escaped the perils of the deep, and died quietly in his bed.

11

Three at Table

The talk in the coffee-room had been of ghosts and apparitions, and nearly everybody present had contributed his mite to the stock of information upon a hazy and somewhat threadbare subject. Opinions ranged from rank incredulity to childlike faith, one believer going so far as to denounce unbelief as impious, with a reference to the Witch of Endor, which was somewhat marred by being complicated in an inexplicable fashion with the story of Jonah.

“Talking of Jonah,” he said solemnly, with a happy disregard of the fact that he had declined to answer several eager questions put to him on the subject, “look at the strange tales sailors tell us.”

“I wouldn’t advise you to believe all those,” said a bluff, clean-shaven man, who had been listening without speaking much. “You see when a sailor gets ashore he’s expected to have something to tell, and his friends would be rather disappointed if he had not.”

“It’s a well-known fact,” interrupted the first speaker fimly, “that sailors are very prone to see visions.”

“They are,” said the other dryly, “they generally see them in pairs, and the shock to the nervous system frequently causes headache next morning.”

“You never saw anything yourself?” suggested an unbeliever.

“Man and boy,” said the other, “I’ve been at sea thirty years, and the only unpleasant incident of that kind occurred in a quiet English countryside.”

“And that?” said another man.

“I was a young man at the time,” said the narrator, drawing at his pipe and glancing good-humouredly at the company. “I had just come back from China, and my own people being away I went down into the country to invite myself to stay with an uncle. When I got down to the place I found it closed and the family in the South of France; but as they were due back in a couple of days I decided to put up at the Royal George, a very decent inn, and await their return.

“The first day I passed well enough; but in the evening the dulness of the rambling old place, in which I was the only visitor, began to weigh upon my spirits, and the next morning after a late breakfast I set out with the intention of having a brisk day’s walk.

“I started off in excellent spirits, for the day was bright and frosty, with a powdering of snow on the iron-bound roads and nipped hedges, and the country had to me all the charm of novelty. It was certainly flat, but there was plenty of timber, and the villages through which I passed were old and picturesque.

“I lunched luxuriously on bread and cheese and beer in the bar of a small inn, and resolved to go a little further before turning back. When at length I found I had gone far enough, I turned up a lane at right angles to the road I was passing, and resolved to find my way back by another route. It is a long lane that has no turning, but this had several, each of which had turnings of its own, which generally led, as I found by trying two or three of them, into the open marshes. Then, tired of lanes, I resolved to rely upon the small compass which hung from my watch chain and go across country home.

“I had got well into the marshes when a white fog, which had been for some time hovering round the edge of the ditches, began gradually to spread. There was no escaping it, but by aid of my compass I was saved from making a circular tour and fell instead into frozen ditches or stumbled over roots in the grass. I kept my course, however, until at four o’clock, when night was coming rapidly up to lend a hand to the fog, I was fain to confess myself lost.

“The compass was now no good to me, and I wandered about miserably, occasi

onally giving a shout on the chance of being heard by some passing shepherd or farmhand. At length by great good luck I found my feet on a rough road driven through the marshes, and by walking slowly and tapping with my stick managed to keep to it. I had followed it for some distance when I heard footsteps approaching me.

“We stopped as we met, and the new arrival, a sturdy-looking countryman, hearing of my plight, walked back with me for nearly a mile, and putting me on to a road-gave me minute instructions how to reach a village some three miles distant.

“I was so tired that three miles sounded like ten, and besides that, a little way off from the road I saw dimly a lighted window. I pointed it out, but my companion shuddered and looked round him uneasily.

“‘You won’t get no good there,’ he said, hastily.

“‘Why not?’ I asked.

“‘There’s a something there, sir,’ he replied, ‘what ’tis I dunno, but the little ’un belonging to a gamekeeper as used to live in these parts see it, and it was never much good afterward. Some say as it’s a poor mad thing, others says as it’s a kind of animal; but whatever it is, it ain’t good to see.’

“‘Well, I’ll keep on, then,’ I said. ‘Good-night.’

“He went back whistling cheerily until his footsteps died away in the distance, and I followed the road he had indicated until it divided into three, any one of which to a stranger might be said to lead straight on. I was now cold and tired, and having half made up my mind, walked slowly back toward the house.

“At first all I could see of it was the little patch of light at the window. I made for that until it disappeared suddenly, and I found myself walking into a tall hedge. I felt my way round this until I came to a small gate, and opening it cautiously, walked, not without some little nervousness, up a long path which led to the door. There was no light and no sound from within. Half repenting of my temerity I shortened my stick and knocked lightly upon the door.

_preview.jpg) Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection)

Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection) The Monkey's Paw

The Monkey's Paw Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II

Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II Odd Craft, Complete

Odd Craft, Complete The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection

The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection Deep Waters, the Entire Collection

Deep Waters, the Entire Collection Three at Table

Three at Table Light Freights

Light Freights Night Watches

Night Watches The Three Sisters

The Three Sisters Ship's Company, the Entire Collection

Ship's Company, the Entire Collection His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts

His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts Fine Feathers

Fine Feathers My Man Sandy

My Man Sandy Self-Help

Self-Help Captains All and Others

Captains All and Others Back to Back

Back to Back More Cargoes

More Cargoes Believe You Me!

Believe You Me! Keeping Up Appearances

Keeping Up Appearances The Statesmen Snowbound

The Statesmen Snowbound An Adulteration Act

An Adulteration Act The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches

The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches Husbandry

Husbandry Love and the Ironmonger

Love and the Ironmonger The Old Man's Bag

The Old Man's Bag Dirty Work

Dirty Work Easy Money

Easy Money The Lady of the Barge

The Lady of the Barge Bedridden and the Winter Offensive

Bedridden and the Winter Offensive Odd Charges

Odd Charges Friends in Need

Friends in Need Watch-Dogs

Watch-Dogs Cupboard Love

Cupboard Love Captains All

Captains All A Spirit of Avarice

A Spirit of Avarice The Nest Egg

The Nest Egg The Guardian Angel

The Guardian Angel The Convert

The Convert Captain Rogers

Captain Rogers Breaking a Spell

Breaking a Spell Striking Hard

Striking Hard The Bequest

The Bequest Shareholders

Shareholders The Weaker Vessel

The Weaker Vessel John Henry Smith

John Henry Smith Four Pigeons

Four Pigeons Made to Measure

Made to Measure For Better or Worse

For Better or Worse Fairy Gold

Fairy Gold Family Cares

Family Cares Good Intentions

Good Intentions Prize Money

Prize Money The Temptation of Samuel Burge

The Temptation of Samuel Burge The Madness of Mr. Lister

The Madness of Mr. Lister The Constable's Move

The Constable's Move Paying Off

Paying Off Double Dealing

Double Dealing A Mixed Proposal

A Mixed Proposal Bill's Paper Chase

Bill's Paper Chase The Changing Numbers

The Changing Numbers Over the Side

Over the Side Lawyer Quince

Lawyer Quince The White Cat

The White Cat Admiral Peters

Admiral Peters The Third String

The Third String The Vigil

The Vigil Bill's Lapse

Bill's Lapse His Other Self

His Other Self Matrimonial Openings

Matrimonial Openings The Substitute

The Substitute Deserted

Deserted Dual Control

Dual Control Homeward Bound

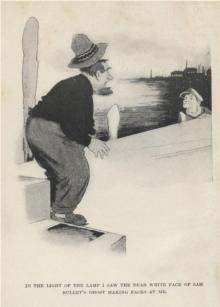

Homeward Bound Sam's Ghost

Sam's Ghost The Unknown

The Unknown Stepping Backwards

Stepping Backwards Sentence Deferred

Sentence Deferred The Persecution of Bob Pretty

The Persecution of Bob Pretty Skilled Assistance

Skilled Assistance A Golden Venture

A Golden Venture Establishing Relations

Establishing Relations A Tiger's Skin

A Tiger's Skin Bob's Redemption

Bob's Redemption Manners Makyth Man

Manners Makyth Man The Head of the Family

The Head of the Family The Understudy

The Understudy Odd Man Out

Odd Man Out Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary

Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence Blundell's Improvement

Blundell's Improvement The Toll-House

The Toll-House Dixon's Return

Dixon's Return Keeping Watch

Keeping Watch The Boatswain's Mate

The Boatswain's Mate The Castaway

The Castaway In the Library

In the Library The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre