- Home

- W. W. Jacobs

Deep Waters, the Entire Collection Page 8

Deep Waters, the Entire Collection Read online

Page 8

Mr. Jernshaw, who was taking the opportunity of a lull in business toweigh out pound packets of sugar, knocked his hands together and stoodwaiting for the order of the tall bronzed man who had just entered theshop--a well-built man of about forty--who was regarding him with blueeyes set in quizzical wrinkles.

"What, Harry!" exclaimed Mr. Jernshaw, in response to the wrinkles."Harry Barrett!"

"That's me," said the other, extending his hand. "The rolling stone comehome covered with moss."

Mr. Jernshaw, somewhat excited, shook hands, and led the way into thelittle parlour behind the shop.

"Fifteen years," said Mr. Barrett, sinking into a chair, "and the oldplace hasn't altered a bit."

"Smithson told me he had let that house in Webb Street to a Barrett,"said the grocer, regarding him, "but I never thought of you. I supposeyou've done well, then?"

Mr. Barrett nodded. "Can't grumble," he said modestly. "I've got enoughto live on. Melbourne's all right, but I thought I'd come home for theevening of my life."

"Evening!" repeated his friend. "Forty-three," said Mr. Barrett,gravely. "I'm getting on."

"You haven't changed much," said the grocer, passing his hand throughhis spare grey whiskers. "Wait till you have a wife and sevenyoungsters. Why, boots alone----"

Mr. Barrett uttered a groan intended for sympathy. "Perhaps you couldhelp me with the furnishing," he said, slowly. "I've never had a placeof my own before, and I don't know much about it."

"Anything I can do," said his friend. "Better not get much yet; youmight marry, and my taste mightn't be hers."

Mr. Barrett laughed. "I'm not marrying," he said, with conviction.

"Seen anything of Miss Prentice yet?" inquired Mr. Jernshaw.

"No," said the other, with a slight flush. "Why?"

"She's still single," said the grocer.

"What of it?" demanded Mr. Barrett, with warmth. "What of it?"

"Nothing," said Mr. Jernshaw, slowly. "Nothing; only I----"

"Well?" said the other, as he paused.

"I--there was an idea that you went to Australia to--to better yourcondition," murmured the grocer. "That--that you were not in a positionto marry--that----"

"Boy and girl nonsense," said Mr. Barrett, sharply. "Why, it's fifteenyears ago. I don't suppose I should know her if I saw her. Is her motheralive?"

"Rather!" said Mr. Jernshaw, with emphasis. "Louisa is something likewhat her mother was when you went away."

Mr. Barrett shivered.

"But you'll see for yourself," continued the other. "You'll have to goand see them. They'll wonder you haven't been before."

"Let 'em wonder," said the embarrassed Mr. Barrett. "I shall go and seeall my old friends in their turn; casual-like. You might let 'em hearthat I've been to see you before seeing them, and then, if they'rethinking any nonsense, it'll be a hint. I'm stopping in town while thehouse is being decorated; next time I come down I'll call and seesomebody else."

"That'll be another hint," assented Mr. Jernshaw. "Not that hints aremuch good to Mrs. Prentice."

"We'll see," said Mr. Barrett.

In accordance with his plan his return to his native town was heraldedby a few short visits at respectable intervals. A sort of humanbutterfly, he streaked rapidly across one or two streets, alighted forhalf an hour to resume an old friendship, and then disappeared again.Having given at least half-a-dozen hints of this kind, he made a finalreturn to Ramsbury and entered into occupation of his new house.

"It does you credit, Jernshaw," he said, gratefully. "I should have madea rare mess of it without your help."

"It looks very nice," admitted his friend. "Too nice."

"That's all nonsense," said the owner, irritably.

"All right," said Mr. Jernshaw. "I don't know the sex, then, that's all.If you think that you're going to keep a nice house like this all toyourself, you're mistaken. It's a home; and where there's a home a womancomes in, somehow."

Mr. Barrett grunted his disbelief.

"I give you four days," said Mr. Jernshaw.

As a matter of fact, Mrs. Prentice and her daughter came on the fifth.Mr. Barrett, who was in an easy-chair, wooing slumber with ahandkerchief over his head, heard their voices at the front door and thecordial invitation of his housekeeper. They entered the room as he sathastily smoothing his rumpled hair.

"Good afternoon," he said, shaking hands.

Mrs. Prentice returned the greeting in a level voice, and, accepting achair, gazed around the room.

"Nice weather," said Mr. Barrett.

"Very," said Mrs. Prentice.

"It's--it's quite a pleasure to see you again," said Mr. Barrett.

"We thought we should have seen you before," said Mrs. Prentice, "but Itold Louisa that no doubt you were busy, and wanted to surprise her. Ilike the carpet; don't you, Louisa?"

Miss Prentice said she did.

"The room is nice and airy," said Mrs. Prentice, "but it's a pity youdidn't come to me before deciding. I could have told you of a betterhouse for the same money."

"I'm very well satisfied with this," said Mr. Barrett. "It's all Iwant."

"It's well enough," conceded Mrs. Prentice, amiably. "And how have youbeen all these years?"

Mr. Barrett, with some haste, replied that his health and spirits hadbeen excellent.

"You look well," said Mrs. Prentice. "Neither of you seem to havechanged much," she added, looking from him to her daughter. "And I thinkyou did quite well not to write. I think it was much the best."

Mr. Barrett sought for a question: a natural, artless question, thatwould neutralize the hideous suggestion conveyed by this remark, but iteluded him. He sat and gazed in growing fear at Mrs. Prentice.

"I--I couldn't write," he said at last, in desperation; "my wife----"

"Your what?" exclaimed Mrs. Prentice, loudly.

"Wife," said Mr. Barrett, suddenly calm now that he had taken theplunge. "She wouldn't have liked it."

Mrs. Prentice tried to control her voice. "I never heard you weremarried!" she gasped. "Why isn't she here?"

"We couldn't agree," said the veracious Mr. Barrett. "She was verydifficult; so I left the children with her and----"

"Chil----" said Mrs. Prentice, and paused, unable to complete the word.

"Five," said Mr. Barrett, in tones of resignation. "It was rather awrench, parting with them, especially the baby. He got his first tooththe day I left."

The information fell on deaf ears. Mrs. Prentice, for once in her lifethoroughly at a loss, sat trying to collect her scattered faculties. Shehad come out prepared for a hard job, but not an impossible one. Allthings considered, she took her defeat with admirable composure.

"I have no doubt it is much the best thing for the children to remainwith their mother," she said, rising.

"Much the best," agreed Mr. Barrett. "Whatever she is like," continuedthe old lady. "Are you ready, Louisa?"

Mr. Barrett followed them to the door, and then, returning to the room,watched, with glad eyes, their progress up the street.

"Wonder whether she'll keep it to herself?" he muttered.

His doubts were set at rest next day. All Ramsbury knew by then of hismatrimonial complications, and seemed anxious to talk about them;complications which tended to increase until Mr. Barrett wrote out alist of his children's names and ages and learnt it off by heart.

Relieved of the attentions of the Prentice family, he walked the streetsa free man; and it was counted to him for righteousness that he neversaid a hard word about his wife. She had her faults, he said, but theywere many thousand miles away, and he preferred to forget them. And headded, with some truth, that he owed her a good deal.

For a few months he had no reason to alter his opinion. Thanks to hispresence of mind, the Prentice family had no terrors for him. Heart-whole and fancy free, he led the easy life of a man of leisure, acondition of things suddenly upset by the arrival of Miss Grace Lindsayto take up a post at the elementary school. Mr. Barrett succu

mbed almostat once, and, after a few encounters in the street and meetings atmutual friends', went to unbosom him-self to Mr. Jernshaw.

"What has she got to do with you?" demanded that gentleman.

"I--I'm rather struck with her," said Mr. Barrett.

"Struck with her?" repeated his friend, sharply. "I'm surprised at you.You've no business to think of such things."

"Why not?" demanded Mr. Barrett, in tones that were sharper still.

"Why not?" repeated the other. "Have you forgotten your wife andchildren?"

Mr. Barrett, who, to do him justice, had forgotten, fell back in hischair and sat gazing at him, open-mouthed.

"You're in a false position--in a way," said Mr. Jernshaw, sternly.

"False is no name for it," said Mr. Barrett, huskily. "What am I to do?"

"Do?" repeated the other, staring at him. "Nothing! Unless, perhaps, yousend for your wife and children. I suppose, in any case, you would haveto have the little ones if anything happened to her?"

Mr. Barrett grinned ruefully.

"Think it over," said Mr. Jernshaw. "I will," said the other, heartily.

He walked home deep in thought. He was a kindly man, and he spent sometime thinking out the easiest death for Mrs. Barrett. He decided at lastupon heart-disease, and a fort-night later all Ramsbury knew of theletter from Australia conveying the mournful intelligence. It wasgenerally agreed that the mourning and the general behaviour of thewidower left nothing to be desired.

"She's at peace at last," he said, solemnly, to Jernshaw.

"I believe you killed her," said his friend. Mr. Barrett startedviolently.

"I mean your leaving broke her heart," explained the other.

Mr. Barrett breathed easily again.

"It's your duty to look after the children," said Jernshaw, firmly. "AndI'm not the only one that thinks so."

"They are with their grandfather and grand-mother," said Mr. Barrett.

Mr. Jernshaw sniffed.

"And four uncles and five aunts," added Mr. Barrett, triumphantly.

"Think how they would brighten up your house," said Mr. Jernshaw.

His friend shook his head. "It wouldn't be fair to their grandmother,"he said, decidedly. "Besides, Australia wants population."

He found to his annoyance that Mr. Jernshaw's statement that he was notalone in his views was correct. Public opinion seemed to expect thearrival of the children, and one citizen even went so far as torecommend a girl he knew, as nurse.

Ramsbury understood at last that his decision was final, and, observinghis attentions to the new schoolmistress, flattered itself that it haddiscovered the reason. It is possible that Miss Lindsay shared theirviews, but if so she made no sign, and on the many occasions on whichshe met Mr. Barrett on her way to and from school greeted him with frankcordiality. Even when he referred to his loneliness, which he didfrequently, she made no comment.

He went into half-mourning at the end of two months, and a month laterbore no outward signs of his loss. Added to that his step was springyand his manner youthful. Miss Lindsay was twenty-eight, and he persuadedhimself that, sexes considered, there was no disparity worth mentioning.

He was only restrained from proposing by a question of etiquette. Even ashilling book on the science failed to state the interval that shouldelapse between the death of one wife and the negotiations for another.It preferred instead to give minute instructions with regard to theeating of asparagus. In this dilemma he consulted Jernshaw.

"Don't know, I'm sure," said that gentle-man; "besides, it doesn'tmatter."

"Doesn't matter?" repeated Mr. Barrett. "Why not?"

"Because I think Tillett is paying her attentions," was the reply. "He'sten years younger than you are, and a bachelor. A girl would naturallyprefer him to a middle-aged widower with five children."

"In Australia," the other reminded him.

"Man for man, bachelor for bachelor," said Mr. Jernshaw, regarding him,"she might prefer you; as things are--"

"I shall ask her," said Mr. Barrett, doggedly. "I was going to wait abit longer, but if there's any chance of her wrecking her prospects forlife by marrying that tailor's dummy it's my duty to risk it--for hersake. I've seen him talking to her twice myself, but I never thoughthe'd dream of such a thing."

Apprehension and indignation kept him awake half the night, but when hearose next morning it was with the firm resolve to put his fortune tothe test that day. At four o'clock he changed his neck-tie for the thirdtime, and at ten past sallied out in the direction of the school. He metMiss Lindsay just coming out, and, after a well-deserved compliment tothe weather, turned and walked with her.

"I was hoping to meet you," he said, slowly.

"Yes?" said the girl.

"I--I have been feeling rather lonely to-day," he continued.

"You often do," said Miss Lindsay, guardedly.

"It gets worse and worse," said Mr. Barrett, sadly.

"I think I know what is the matter with you," said the girl, in a softvoice; "you have got nothing to do all day, and you live alone, exceptfor your housekeeper."

Mr. Barrett assented with some eagerness, and stole a hopeful glance ather.

"You--you miss something," continued Miss. Lindsay, in a falteringvoice.

"I do," said Mr. Barrett, with ardour.

"You miss"--the girl made an effort--"you miss the footsteps and voicesof your little children."

Mr. Barrett stopped suddenly in the street, and then, with a jerk, wentblindly on.

"I've never spoken of it before because it's your business, not mine,"continued the girl. "I wouldn't have spoken now, but when you referredto your loneliness I thought perhaps you didn't realize the cause ofit."

Mr. Barrett walked on in silent misery.

"Poor little motherless things!" said Miss Lindsay, softly. "Motherlessand--fatherless."

"Better for them," said Mr. Barrett, finding his voice at last.

"It almost looks like it," said Miss Lindsay, with a sigh.

Mr. Barrett tried to think clearly, but the circumstances were hardlyfavourable. "Suppose," he said, speaking very slowly, "suppose I wantedto get married?"

Miss Lindsay started. "What, again?" she said, with an air of surprise.

"How could I ask a girl to come and take over five children?"

"No woman that was worth having would let little children be sacrificedfor her sake," said Miss Lindsay, decidedly.

"Do you think anybody would marry me with five children?" demanded Mr.Barrett.

"She might," said the girl, edging away from him a little. "It dependson the woman."

"Would--you, for instance?" said Mr. Barrett, desperately.

Miss Lindsay shrank still farther away. "I don't know; it would dependupon circumstances," she murmured.

"I will write and send for them," said Mr. Barrett, significantly.

Miss Lindsay made no reply. They had arrived at her gate by this time,and, with a hurried handshake, she disappeared indoors.

Mr. Barrett, somewhat troubled in mind, went home to tea.

He resolved, after a little natural hesitation, to drown the children,and reproached himself bitterly for not having disposed of them at thesame time as their mother. Now he would have to go through anotherperiod of mourning and the consequent delay in pressing his suit.Moreover, he would have to allow a decent interval between hisconversation with Miss Lindsay and their untimely end.

The news of the catastrophe arrived two or three days before the returnof the girl from her summer holidays. She learnt it in the first half-hour from her landlady, and sat in a dazed condition listening to adescription of the grief-stricken father and the sympathy extended tohim by his fellow-citizens. It appeared that nothing had passed his lipsfor two days.

"Shocking!" said Miss Lindsay, briefly. "Shocking!"

An instinctive feeling that the right and proper thing to do was tonurse his grief in solitude kept Mr. Barrett out of her way for nearly aweek. When she did meet h

im she received a limp handshake and a greetingin a voice from which all hope seemed to have departed.

"I am very sorry," she said, with a sort of measured gentleness.

Mr. Barrett, in his hushed voice, thanked her.

"I am all alone now," he said, pathetically. "There is nobody now tocare whether I live or die."

Miss Lindsay did not contradict him.

"How did it happen?" she inquired, after they had gone some distance insilence.

"They were out in a sailing-boat," said Mr. Barrett; "the boat capsizedin a puff of wind, and they were all drowned."

"Who was in charge of them?" inquired the girl, after a decent interval.

"Boatman," replied the other.

"How did you hear?"

"I had a letter from one of my sisters-in-law, Charlotte," said Mr.Barrett. "A most affecting letter. Poor Charlotte was like a secondmother to them. She'll never be the same woman again. Never!"

"I should like to see the letter," said Miss Lindsay, musingly.

Mr. Barrett suppressed a start. "I should like to show it to you," hesaid, "but I'm afraid I have destroyed it. It made me shudder every timeI looked at it."

"It's a pity," said the girl, dryly. "I should have liked to see it.I've got my own idea about the matter. Are you sure she was very fond ofthem?"

"She lived only for them," said Mr. Barrett, in a rapt voice.

"Exactly. I don't believe they are drowned at all," said Miss Lindsay,suddenly. "I believe you have had all this terrible anguish for nothing.It's too cruel."

Mr. Barrett stared at her in anxious amazement.

"I see it all now," continued the girl. "Their Aunt Charlotte wasdevoted to them. She always had the fear that some day you would returnand claim them, and to prevent that she invented the story of theirdeath."

"Charlotte is the most truthful woman that ever breathed," said thedistressed Mr. Barrett.

Miss Lindsay shook her head. "You are like all other honourable,truthful people," she said, looking at him gravely. "You can't imagineanybody else telling a falsehood. I don't believe you could tell one ifyou tried."

Mr. Barrett gazed about him with the despairing look of a drowningmariner.

"I'm certain I'm right," continued the girl. "I can see Charlotteexulting in her wickedness. Why!"

"What's the matter?" inquired Mr. Barrett, greatly worried.

"I've just thought of it," said Miss Lindsay. "She's told you that yourchildren are drowned, and she has probably told them you are dead. Awoman like that would stick at nothing to gain her ends."

"You don't know Charlotte," said Mr. Barrett, feebly.

"I think I do," was the reply. "However, we'll make sure. I supposeyou've got friends in Melbourne?"

"A few," said Mr. Barrett, guardedly.

"Come down to the post-office and cable to one of them."

Mr. Barrett hesitated. "I'll write," he said, slowly. "It's an awkwardthing to cable; and there's no hurry. I'll write to Jack Adams, Ithink."

"It's no good writing," said Miss Lindsay, firmly. "You ought to knowthat."

"Why not?" demanded the other.

"Because, you foolish man," said the girl, calmly, "before your lettergot there, there would be one from Melbourne saying that he had beenchoked by a fish-bone, or died of measles, or something of that sort."

Mr. Barrett, hardly able to believe his ears, stopped short and lookedat her. The girl's eyes were moist with mirth and her lips trembling. Heput out his hand and took her wrist in a strong grip.

"That's all right," he said, with a great gasp of relief. "Phew! At onetime I thought I had lost you."

"By heart-disease, or drowning?" inquired Miss Lindsay, softly.

THE WINTER OFFENSIVE

_preview.jpg) Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection)

Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection) The Monkey's Paw

The Monkey's Paw Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II

Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II Odd Craft, Complete

Odd Craft, Complete The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection

The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection Deep Waters, the Entire Collection

Deep Waters, the Entire Collection Three at Table

Three at Table Light Freights

Light Freights Night Watches

Night Watches The Three Sisters

The Three Sisters Ship's Company, the Entire Collection

Ship's Company, the Entire Collection His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts

His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts Fine Feathers

Fine Feathers My Man Sandy

My Man Sandy Self-Help

Self-Help Captains All and Others

Captains All and Others Back to Back

Back to Back More Cargoes

More Cargoes Believe You Me!

Believe You Me! Keeping Up Appearances

Keeping Up Appearances The Statesmen Snowbound

The Statesmen Snowbound An Adulteration Act

An Adulteration Act The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches

The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches Husbandry

Husbandry Love and the Ironmonger

Love and the Ironmonger The Old Man's Bag

The Old Man's Bag Dirty Work

Dirty Work Easy Money

Easy Money The Lady of the Barge

The Lady of the Barge Bedridden and the Winter Offensive

Bedridden and the Winter Offensive Odd Charges

Odd Charges Friends in Need

Friends in Need Watch-Dogs

Watch-Dogs Cupboard Love

Cupboard Love Captains All

Captains All A Spirit of Avarice

A Spirit of Avarice The Nest Egg

The Nest Egg The Guardian Angel

The Guardian Angel The Convert

The Convert Captain Rogers

Captain Rogers Breaking a Spell

Breaking a Spell Striking Hard

Striking Hard The Bequest

The Bequest Shareholders

Shareholders The Weaker Vessel

The Weaker Vessel John Henry Smith

John Henry Smith Four Pigeons

Four Pigeons Made to Measure

Made to Measure For Better or Worse

For Better or Worse Fairy Gold

Fairy Gold Family Cares

Family Cares Good Intentions

Good Intentions Prize Money

Prize Money The Temptation of Samuel Burge

The Temptation of Samuel Burge The Madness of Mr. Lister

The Madness of Mr. Lister The Constable's Move

The Constable's Move Paying Off

Paying Off Double Dealing

Double Dealing A Mixed Proposal

A Mixed Proposal Bill's Paper Chase

Bill's Paper Chase The Changing Numbers

The Changing Numbers Over the Side

Over the Side Lawyer Quince

Lawyer Quince The White Cat

The White Cat Admiral Peters

Admiral Peters The Third String

The Third String The Vigil

The Vigil Bill's Lapse

Bill's Lapse His Other Self

His Other Self Matrimonial Openings

Matrimonial Openings The Substitute

The Substitute Deserted

Deserted Dual Control

Dual Control Homeward Bound

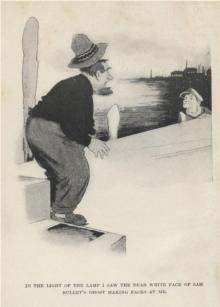

Homeward Bound Sam's Ghost

Sam's Ghost The Unknown

The Unknown Stepping Backwards

Stepping Backwards Sentence Deferred

Sentence Deferred The Persecution of Bob Pretty

The Persecution of Bob Pretty Skilled Assistance

Skilled Assistance A Golden Venture

A Golden Venture Establishing Relations

Establishing Relations A Tiger's Skin

A Tiger's Skin Bob's Redemption

Bob's Redemption Manners Makyth Man

Manners Makyth Man The Head of the Family

The Head of the Family The Understudy

The Understudy Odd Man Out

Odd Man Out Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary

Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence Blundell's Improvement

Blundell's Improvement The Toll-House

The Toll-House Dixon's Return

Dixon's Return Keeping Watch

Keeping Watch The Boatswain's Mate

The Boatswain's Mate The Castaway

The Castaway In the Library

In the Library The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre