- Home

- W. W. Jacobs

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre Page 8

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre Read online

Page 8

He went down the garden as soon as it was light and completed his work. Then he went indoors to breakfast and to announce his plans for sudden departure to Mrs Howe, his white and twitching face amply corroborating his tale of neuralgia and want of sleep.

“Things’ll be all right,” said the woman. “I’ll ask the police to keep an eye on the house of a night. I did speak to one last night about them brutes as destroyed the rockery. If they try it again they may get a surprise.”

Keller quivered but made no sign. He went upstairs and packed his bag, and two hours later was in the train on his way to Exeter, where he proposed to stay the night. After that, Cornwall, perhaps.

He secured a room at an hotel and went for a stroll to pass the time before dinner. How happy the people in the streets seemed to be, even the poorest! All free and all sure of their freedom. They could eat and sleep and enjoy the countless trivial things that make up life. Of battle and murder and sudden death they had no thought.

The light and bustle of the dining-room gave him a little comfort. After his lonely nights it was good to know that there were people all around him, that the house would be full of them whilst he slept. He felt that he was beginning a fresh existence. In future he would live amongst a crowd.

It was late when he went upstairs, but he lay awake for a few minutes. A faint sound or two reached him from downstairs, and the movements of somebody in the next room gave him a comfortable feeling of security. With a sigh of content he fell asleep.

He was awakened by a knocking; a knocking which sounded just above the head of his bed and died away almost before he had brushed the sleep from his eyes. He looked around fearfully, and then, lighting his candle, lay listening. The noise was not repeated. He had been dreaming, but he could not remember the substance of his dream. It had been unpleasant, but vague. More than unpleasant, terrifying. Somebody had been shouting at him. Shouting!

He fell back with a groan. The faint hopes of the night before died within him. He had been shouting and the strange noise came from the occupant of the next room. What had he said? and what had his neighbour heard?

He slept no more. From somewhere below he heard a clock toll the hours, and, tossing in his bed, wondered how many more remained to him.

Day came at last and he descended to breakfast. The hour was early and only two other tables were occupied, from one of which, between mouthfuls, a bluff-looking, elderly man eyed him curiously. He caught Keller’s eye at last and spoke.

“Better?” he inquired.

Keller tried to force his quivering lips to a smile.

“Stood it as long as I could,” said the other; “then I knocked. I thought perhaps you were delirious. Same words over and over again; sounded like ‘Mockery’ and ‘Mortal,’ ‘Mockery’ and ‘Mortal.’ You must have used them a hundred times.”

Keller finished his coffee, and, lighting a cigarette, went and sat in the lounge. He had made his bid for freedom and failed. He looked up the times of the trains to town and rang for his bill.

– IV –

He was back in the silent house, upon which, in the fading light of the summer evening, a great stillness seemed to have descended. The atmosphere of horror had gone and left only a sense of abiding peace. All fear had left him, and pain and remorse had gone with it. Serene and tranquil he went into the fatal room, and, opening the window, sat by it, watching the succession of shadowy tableaux that had been his life. Some of it good and some of it bad, but most of it neither good nor bad. A very ordinary life until fate had linked it for all time with that of Martle’s. He was a living man bound to a corpse with bonds that could never be severed.

It grew dark and he lit the gas and took a volume of poems from the shelves. Never before had he read with such insight and appreciation. In some odd fashion all his senses seemed to have been sharpened and refined.

He read for an hour, and then, replacing the book, went slowly upstairs. For a long time he lay in bed thinking and trying to analyse the calm and indifference which had overtaken him and, with the problem still unsolved, fell asleep.

For a time he dreamt, but of pleasant, happy things. He seemed to be filled with a greater content than he had ever known before, a content which did not leave him even when these dreams faded and he found himself back in the old one.

This time, however, it was different. He was still digging, but not in a state of frenzy and horror. He dug because something told him it was his duty to dig, and only by digging could he make reparation. And it was a matter of no surprise to him that Martle stood close by looking on. Not the Martle he had known, nor a bloody and decaying Martle, but one of grave and noble aspect. And there was a look of understanding on his face that nearly made Keller weep.

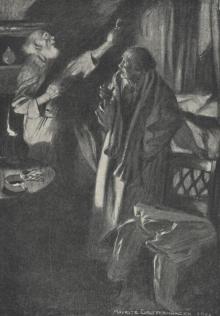

He went on digging with a sense of companionship such as he had never known before. Then suddenly, without warning, the sun blazed out of the darkness and struck him full in the face. The light was unbearable, and with a wild cry he dropped his spade and clapped his hands over his eyes. The light went, and a voice spoke to him out of the darkness.

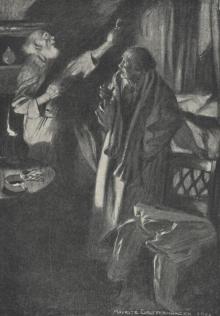

He opened his eyes on a dim figure standing a yard or two away.

“Hope I didn’t frighten you, sir,” said the voice. “I called to you once or twice and then I guessed you were doing this in your sleep.”

“In my sleep,” repeated Keller. “Yes.”

“And a pretty mess you’ve made of it,” said the constable, with a genial chuckle. “Lord! to think of you working at it every day and then pulling it down every night. Shouted at you I did, but you wouldn’t wake.”

He turned on the flashlight that had dazzled Keller, and surveyed the ruins. Keller stood by, motionless—and waiting.

“Looks like an earthquake,” muttered the constable. He paused, and kept the light directed upon one spot. Then he stooped down and scratched away the earth with his fingers, and tugged. He stood up suddenly and turned the light on Keller, while with the other he fumbled in his pocket. He spoke in a voice cold and official.

“Are you coming quietly?” he asked.

Keller stepped towards him with both hands outstretched.

“I am coming quietly,” he said, in a low voice. “Thank God!”

7

The Interruption

– I –

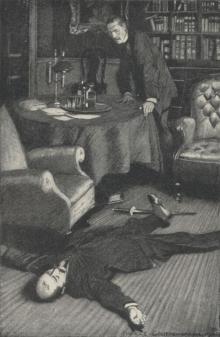

The last of the funeral guests had gone and Spencer Goddard, in decent black, sat alone in his small, well-furnished study. There was a queer sense of freedom in the house since the coffin had left it; the coffin which was now hidden in its solitary grave beneath the yellow earth. The air, which for the last three days had seemed stale and contaminated, now smelt fresh and clean. He went to the open window and, looking into the fading light of the autumn day, took a deep breath.

He closed the window and, stooping down, put a match to the fire, and, dropping into his easy chair, sat listening to the cheery crackle of the wood. At the age of thirty-eight he had turned over a fresh page. Life, free and unencumbered, was before him. His dead wife’s money was at last his, to spend as he pleased, instead of being doled out in reluctant driblets.

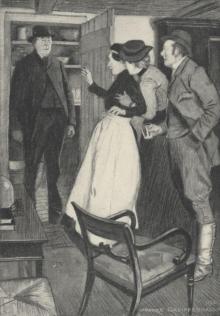

He turned at a step at the door and his face assumed the appearance of gravity and sadness it had worn for the last four days. The cook, with the same air of decorous grief, entered the room quietly and, crossing to the mantelpiece, placed upon it a photograph.

“I thought you’d like to have it, sir,” she said, in a low voice, “to remind you.”

Goddard thanked her, and, rising, took it in his hand and stood regarding it. He noticed with satisfaction that his hand was absolutely steady.

“It is a very good likeness—till she was taken ill,” continued the woman. “I never saw anybody change so sudden.”

“The nature of her disease, Hannah,” said her master.

The woman nodded, and, dabbing at her eyes with her handkerchief, stood regarding him.

“Is there anything you want?” he inquired, after a time.

She shook her head. “I can’t believe she’s gone,” she

said, in a low voice. “Every now and then I have a queer feeling that she’s still here—”

“It’s your nerves,” said her master sharply.

“—and wanting to tell me something.”

By a great effort Goddard refrained from looking at her.

“Nerves,” he said again. “Perhaps you ought to have a little holiday. It has been a great strain upon you.”

“You, too, sir,” said the woman respectfully. “Waiting on her hand and foot as you have done, I can’t think how you stood it. If you’d only had a nurse—”

“I preferred to do it myself, Hannah,” said her master. “If I had had a nurse it would have alarmed her.”

The woman assented. “And they are always peeking and prying into what doesn’t concern them,” she added. “Always think they know more than the doctors do.”

Goddard turned a slow look upon her. The tall, angular figure was standing in an attitude of respectful attention; the cold slaty-brown eyes were cast down, the sullen face expressionless.

“She couldn’t have had a better doctor,” he said, looking at the fire again. “No man could have done more for her.”

“And nobody could have done more for her than you did, sir,” was the reply. “There’s few husbands that would have done what you did.”

Goddard stiffened in his chair. “That will do, Hannah,” he said curtly.

“Or done it so well,” said the woman, with measured slowness.

With a strange, sinking sensation, her master paused to regain his control. Then he turned and eyed her steadily. “Thank you,” he said slowly; “you mean well, but at present I cannot discuss it.”

For some time after the door had closed behind her he sat in deep thought. The feeling of well-being of a few minutes before had vanished, leaving in its place an apprehension which he refused to consider, but which would not be allayed. He thought over his actions of the last few weeks, carefully, and could remember no flaw. His wife’s illness, the doctor’s diagnosis, his own solicitous care, were all in keeping with the ordinary. He tried to remember the woman’s exact words—her manner. Something had shown him Fear. What?

He could have laughed at his fears next morning. The dining-room was full of sunshine and the fragrance of coffee and bacon was in the air. Better still, a worried and commonplace Hannah. Worried over two eggs with false birth certificates, over the vendor of which she became almost lyrical.

“The bacon is excellent,” said her smiling master, “so is the coffee; but your coffee always is.”

Hannah smiled in return, and, taking fresh eggs from a rosy-cheeked maid, put them before him.

A pipe, followed by a brisk walk, cheered him still further. He came home glowing with exercise and again possessed with that sense of freedom and freshness. He went into the garden—now his own—and planned alterations.

After lunch he went over the house. The windows of his wife’s bedroom were open and the room neat and airy. His glance wandered from the made-up bed to the brightly polished furniture. Then he went to the dressing-table and opened the drawers, searching each in turn. With the exception of a few odds and ends they were empty. He went out on to the landing and called for Hannah.

“Do you know whether your mistress locked up any of her things?” he inquired.

“What things?” said the woman.

“Well, her jewellery mostly.”

“Oh!” Hannah smiled. “She gave it all to me,” she said quietly.

Goddard checked an exclamation. His heart was beating nervously, but he spoke sternly.

“When?”

“Just before she died—of gastro-enteritis,” said the woman.

There was a long silence. He turned and with great care mechanically closed the drawers of the dressing-table. The tilted glass showed him the pallor of his face, and he spoke without turning round.

“That is all right, then,” he said huskily. “I only wanted to know what had become of it. I thought, perhaps, Milly—”

Hannah shook her head. “Milly’s all right,” she said, with a strange smile. “She’s as honest as we are. Is there anything more you want, sir?”

She closed the door behind her with the quietness of the well-trained servant; Goddard, steadying himself with his hand on the rail of the bed, stood looking into the future.

– II –

The days passed monotonously, as they pass with a man in prison. Gone was the sense of freedom and the idea of a wider life. Instead of a cell, a house with ten rooms—but Hannah, the jailer, guarding each one. Respectful and attentive, the model servant, he saw in every word a threat against his liberty—his life. In the sullen face and cold eyes he saw her knowledge of power; in her solicitude for his comfort and approval, a sardonic jest. It was the master playing at being the servant. The years of unwilling servitude were over, but she felt her way carefully with infinite zest in the game. Warped and bitter, with a cleverness which had never before had scope, she had entered into her kingdom. She took it little by little, savouring every morsel.

“I hope I’ve done right, sir,” she said one morning. “I have given Milly notice.”

Goddard looked up from his paper. “Isn’t she satisfactory?” he inquired.

“Not to my thinking, sir,” said the woman. “And she says she is coming to see you about it. I told her that would be no good.”

“I had better see her and hear what she has to say,” said her master.

“Of course, if you wish to,” said Hannah; “only, after giving her notice, if she doesn’t go I shall. I should be sorry to go—I’ve been very comfortable here—but it’s either her or me.

“I should be sorry to lose you,” said Goddard in a hopeless voice.

“Thank you, sir,” said Hannah. “I’m sure I’ve tried to do my best. I’ve been with you some time now—and I know all your little ways. I expect I understand you better than anybody else would. I do all I can to make you comfortable.”

“Very well, I leave it to you,” said Goddard in a voice which strove to be brisk and commanding. “You have my permission to dismiss her.”

“There’s another thing I wanted to see you about,” said Hannah; “my wages. I was going to ask for a rise, seeing that I’m really house-keeper here now.”

“Certainly,” said her master, considering, “that only seems fair. Let me see—what are you getting?”

“Thirty-six.”

Goddard reflected for a moment and then turned with a benevolent smile. “Very well,” he said cordially, “I’ll make it forty-two. That’s ten shillings a month more.”

“I was thinking of a hundred,” said Hannah dryly.

The significance of the demand appalled him. “Rather a big jump,” he said at last. “I really don’t know that I—”

“It doesn’t matter,” said Hannah. “I thought I was worth it—to you—that’s all. You know best. Some people might think I was worth two hundred. That’s a bigger jump, but after all a big jump is better than—”

She broke off and tittered. Goddard eyed her.

“—than a big drop,” she concluded.

Her master’s face set. The lips almost disappeared and something came into the pale eyes that was revolting. Still eyeing her, he rose and approached her. She stood her ground and met him eye to eye.

“You are jocular,” he said at last.

“Short life and a merry one,” said the woman.

“Mine or yours?”

“Both, perhaps,” was the reply.

“If—if I give you a hundred,” said Goddard, moistening his lips, “that ought to make your life merrier, at any rate.”

Hannah nodded. “Merry and long, perhaps,” she said slowly. “I’m careful, you know—very careful.”

“I am sure you are,” said Goddard, his face relaxing.

“Careful what I eat and drink, I mean,” said the woman, eyeing him steadily.

“That is wise,” he said slowly. “I am myself—that is why I am payin

g a good cook a large salary. But don’t overdo things, Hannah; don’t kill the goose that lays the golden eggs.”

“I am not likely to do that,” she said coldly. “Live and let live; that is my motto. Some people have different ones. But I’m careful; nobody won’t catch me napping. I’ve left a letter with my sister, in case.”

Goddard turned slowly and in a casual fashion put the flowers straight in a bowl on the table, and, wandering to the window, looked out. His face was white again and his hands trembled.

“To be opened after my death,” continued Hannah. “I don’t believe in doctors—not after what I’ve seen of them—I don’t think they know enough; so if I die I shall be examined. I’ve given good reasons.”

“And suppose,” said Goddard, coming from the window, “suppose she is curious, and opens it before you die?”

“We must chance that,” said Hannah, shrugging her shoulders; “but I don’t think she will. I sealed it up with sealing-wax, with a mark on it.”

“She might open it and say nothing about it,” persisted her master.

An unwholesome grin spread slowly over Hannah’s features. “I should know it soon enough,” she declared boisterously, “and so would other people. Lord! there would be an upset! Chidham would have something to talk about for once. We should be in the paper—both of us.”

Goddard forced a smile. “Dear me!” he said gently. “Your pen seems to be a dangerous weapon, Hannah, but I hope that the need to open it will not happen for another fifty years. You look well and strong.”

The woman nodded. “I don’t take up my troubles before they come,” she said, with a satisfied air; “but there’s no harm in trying to prevent them coming. Prevention is better than cure.”

“Exactly,” said her master; “and, by the way, there’s no need for this little financial arrangement to be known by anybody else. I might become unpopular with my neighbours for setting a bad example. Of course, I am giving you this sum because I really think you are worth it.”

_preview.jpg) Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection)

Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection) The Monkey's Paw

The Monkey's Paw Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II

Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II Odd Craft, Complete

Odd Craft, Complete The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection

The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection Deep Waters, the Entire Collection

Deep Waters, the Entire Collection Three at Table

Three at Table Light Freights

Light Freights Night Watches

Night Watches The Three Sisters

The Three Sisters Ship's Company, the Entire Collection

Ship's Company, the Entire Collection His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts

His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts Fine Feathers

Fine Feathers My Man Sandy

My Man Sandy Self-Help

Self-Help Captains All and Others

Captains All and Others Back to Back

Back to Back More Cargoes

More Cargoes Believe You Me!

Believe You Me! Keeping Up Appearances

Keeping Up Appearances The Statesmen Snowbound

The Statesmen Snowbound An Adulteration Act

An Adulteration Act The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches

The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches Husbandry

Husbandry Love and the Ironmonger

Love and the Ironmonger The Old Man's Bag

The Old Man's Bag Dirty Work

Dirty Work Easy Money

Easy Money The Lady of the Barge

The Lady of the Barge Bedridden and the Winter Offensive

Bedridden and the Winter Offensive Odd Charges

Odd Charges Friends in Need

Friends in Need Watch-Dogs

Watch-Dogs Cupboard Love

Cupboard Love Captains All

Captains All A Spirit of Avarice

A Spirit of Avarice The Nest Egg

The Nest Egg The Guardian Angel

The Guardian Angel The Convert

The Convert Captain Rogers

Captain Rogers Breaking a Spell

Breaking a Spell Striking Hard

Striking Hard The Bequest

The Bequest Shareholders

Shareholders The Weaker Vessel

The Weaker Vessel John Henry Smith

John Henry Smith Four Pigeons

Four Pigeons Made to Measure

Made to Measure For Better or Worse

For Better or Worse Fairy Gold

Fairy Gold Family Cares

Family Cares Good Intentions

Good Intentions Prize Money

Prize Money The Temptation of Samuel Burge

The Temptation of Samuel Burge The Madness of Mr. Lister

The Madness of Mr. Lister The Constable's Move

The Constable's Move Paying Off

Paying Off Double Dealing

Double Dealing A Mixed Proposal

A Mixed Proposal Bill's Paper Chase

Bill's Paper Chase The Changing Numbers

The Changing Numbers Over the Side

Over the Side Lawyer Quince

Lawyer Quince The White Cat

The White Cat Admiral Peters

Admiral Peters The Third String

The Third String The Vigil

The Vigil Bill's Lapse

Bill's Lapse His Other Self

His Other Self Matrimonial Openings

Matrimonial Openings The Substitute

The Substitute Deserted

Deserted Dual Control

Dual Control Homeward Bound

Homeward Bound Sam's Ghost

Sam's Ghost The Unknown

The Unknown Stepping Backwards

Stepping Backwards Sentence Deferred

Sentence Deferred The Persecution of Bob Pretty

The Persecution of Bob Pretty Skilled Assistance

Skilled Assistance A Golden Venture

A Golden Venture Establishing Relations

Establishing Relations A Tiger's Skin

A Tiger's Skin Bob's Redemption

Bob's Redemption Manners Makyth Man

Manners Makyth Man The Head of the Family

The Head of the Family The Understudy

The Understudy Odd Man Out

Odd Man Out Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary

Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence Blundell's Improvement

Blundell's Improvement The Toll-House

The Toll-House Dixon's Return

Dixon's Return Keeping Watch

Keeping Watch The Boatswain's Mate

The Boatswain's Mate The Castaway

The Castaway In the Library

In the Library The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre