- Home

- W. W. Jacobs

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre Page 9

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre Read online

Page 9

“I’m sure you do,” said Hannah. “I’m not sure I ain’t worth more, but this’ll do to go on with. I shall get a girl for less than we are paying Milly, and that’ll be another little bit extra for me.”

“Certainly,” said Goddard, and smiled again.

“Come to think of it,” said Hannah, pausing at the door, “I ain’t sure I shall get anybody else; then there’ll be more than ever for me. If I do the work I might as well have the money.”

Her master nodded, and, left to himself, sat down to think out a position which was as intolerable as it was dangerous. At a great risk he had escaped from the dominion of one woman only to fall, bound and helpless, into the hands of another. However vague and unconvincing the suspicions of Hannah might be, they would be sufficient. Evidence could be unearthed. Cold with fear one moment, and hot with fury the next, he sought in vain for some avenue of escape. It was his brain against that of a cunning, illiterate fool; a fool whose malicious stupidity only added to his danger. And she drank. With largely increased wages she would drink more and his very life might depend upon a hiccuped boast. It was clear that she was enjoying her supremacy; later on her vanity would urge her to display it before others. He might have to obey the crack of her whip before witnesses, and that would cut off all possibility of escape.

He sat with his head in his hands. There must be a way out and he must find it. Soon. He must find it before gossip began; before the changed position of master and servant lent colour to her story when that story became known. Shaking with fury, he thought of her lean, ugly throat and the joy of choking her life out with his fingers. He started suddenly, and took a quick breath. No, no fingers—a rope.

– III –

Bright and cheerful outside and with his friends, in the house he was quiet and submissive. Milly had gone, and, if the service was poorer and the rooms neglected, he gave no sign. If a bell remained unanswered he made no complaint, and to studied insolence turned the other cheek of politeness. When at this tribute to her power the woman smiled, he smiled in return. A smile which, for all its disarming softness, left her vaguely uneasy.

“I’m not afraid of you,” she said once, with a menacing air.

“I hope not,” said Goddard in a slightly surprised voice.

“Some people might be, but I’m not,” she declared. “If anything happened to me—”

“Nothing could happen to such a careful woman as you are,” he said, smiling again. “You ought to live to ninety—with luck.”

It was clear to him that the situation was getting on his nerves. Unremembered but terrible dreams haunted his sleep. Dreams in which some great, inevitable disaster was always pressing upon him, although he could never discover what it was. Each morning he awoke unrefreshed to face another day of torment. He could not meet the woman’s eyes for fear of revealing the threat that was in his own.

Delay was dangerous and foolish. He had thought out every move in that contest of wits which was to remove the shadow of the rope from his own neck and place it about that of the woman. There was a little risk, but the stake was a big one. He had but to set the ball rolling and others would keep it on its course. It was time to act.

He came in a little jaded from his afternoon walk, and left his tea untouched. He ate but little dinner, and, sitting hunched up over the fire, told the woman that he had taken a slight chill. Her concern, he felt grimly, might have been greater if she had known the cause.

He was no better next day, and after lunch called in to consult his doctor. He left with a clean bill of health except for a slight digestive derangement, the remedy for which he took away with him in a bottle. For two days he swallowed one tablespoonful three times a day in water, without result, then he took to his bed.

“A day or two in bed won’t hurt you,” said the doctor. “Show me that tongue of yours again.”

“But what is the matter with me, Roberts?” inquired the patient.

The doctor pondered. “Nothing to trouble about—nerves a bit wrong—digestion a little bit impaired. You’ll be all right in a day or two.”

Goddard nodded. So far, so good; Roberts had not outlived his usefulness. He smiled grimly after the doctor had left at the surprise he was preparing for him. A little rough on Roberts and his professional reputation, perhaps, but these things could not be avioded.

He lay back and visualized the programme. A day or two longer, getting gradually worse, then a little sickness. After that a nervous, somewhat shamefaced patient hinting at things. His food had a queer taste—he felt worse after taking it; he knew it was ridiculous, still—there was some of his beef tea he had put aside, perhaps the doctor would like to examine it? and the medicine? Secretions, too; perhaps he would like to see those?

Propped on his elbow, he stared fixedly at the wall. There would be a trace—a faint trace—of arsenic in the secretions. There would be more than a trace in the other things. An attempt to poison him would be clearly indicated, and—his wife’s symptoms had resembled his own—let Hannah get out of the web he was spinning if she could. As for the letter she had threatened him with, let her produce it; it could only recoil upon herself. Fifty letters could not save her from the doom he was preparing for her. It was her life or his, and he would show no mercy. For three days he doctored himself with sedulous care, watching himself anxiously the while. His nerve was going and he knew it. Before him was the strain of the discovery, the arrest, and the trial. The gruesome business of his wife’s death. A long business. He would wait no longer, and he would open the proceedings with dramatic suddenness.

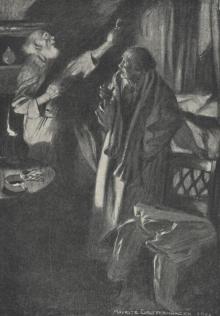

It was between nine and ten o’clock at night when he rang his bell, and it was not until he had rung four times that he heard the heavy steps of Hannah mounting the stairs.

“What d’you want?” she demanded, standing in the doorway.

“I’m very ill,” he said, gasping. “Run for the doctor. Quick!”

The woman stared at him in genuine amazement. “What, at this time o’ night?” she exclaimed. “Not likely.”

“I’m dying!” said Goddard in a broken voice.

“Not you,” she said roughly. “You’ll be better in the morning.”

“I’m dying,” he repeated. “Go—for—the—doctor.”

The woman hesitated. The rain beat in heavy squalls against the window, and the doctor’s house was a mile distant on the lonely road. She glanced at the figure on the bed.

“I should catch my death o’ cold,” she grumbled.

She stood sullenly regarding him. He certainly looked very ill, and his death would by no means benefit her. She listened, scowling, to the wind and the rain.

“All right,” she said at last, and went noisily from the room.

His face set in a mirthless smile, he heard her bustling about below. The front door slammed violently and he was alone.

He waited for a few minutes and then, getting out of bed, put on his dressing-gown and set about his preparations. With a steady hand he added a little white powder to the remains of his beef-tea and to the contents of his bottle of medicine. He stood listening a moment at some faint sound from below, and, having satisfied himself, lit a candle and made his way to Hannah’s room. For a space he stood irresolute, looking about him. Then he opened one of the drawers and, placing the broken packet of powder under a pile of clothing at the back, made his way back to bed.

He was disturbed to find that he was trembling with excitement and nervousness. He longed for tobacco, but that was impossible. To reassure himself he began to rehearse his conversation with the doctor, and again he thought over every possible complication. The scene with the woman would be terrible; he would have to be too ill to take any part in it. The less he said the better. Others would do all that was necessary.

He lay for a long time listening to the sound of the wind and the rain. Inside, the house seemed unusually quiet, and with an odd sensation he suddenly realized that it was the first time he had been alone in it since his wife’s death. H

e remembered that she would have to be disturbed. The thought was unwelcome. He did not want her to be disturbed. Let the dead sleep.

He sat up in bed and drew his watch from beneath the pillow. Hannah ought to have been back before; in any case she could not be long now. At any moment he might hear her key in the lock. He lay down again and reminded himself that things were shaping well. He had shaped them, and some of the satisfaction of the artist was his.

The silence was oppressive. The house seemed to be listening, waiting. He looked at his watch again and wondered, with a curse, what had happened to the woman. It was clear that the doctor must be out, but that was no reason for her delay. It was close on midnight, and the atmosphere of the house seemed in some strange fashion to be brooding and hostile.

In a lull in the wind he thought he heard footsteps outside, and his face cleared as he sat up listening for the sound of the key in the door below. In another moment the woman would be in the house and the fears engendered by a disordered fancy would have flown. The sound of the steps had ceased, but he could hear no sound of entrance. Until all hope had gone, he sat listening. He was certain he had heard footsteps. Whose?

Trembling and haggard he sat waiting, assailed by a crowd of murmuring fears. One whispered that he had failed and would have to pay the penalty of failing; that he had gambled with death and lost.

By a strong effort he fought down these fancies and, closing his eyes, tried to compose himself to rest. It was evident now that the doctor was out and that Hannah was waiting to return with him in his car. He was frightening himself for nothing. At any moment he might hear the sound of their arrival.

He heard something else, and, sitting up suddenly, tried to think what it was and what had caused it. It was a very faint sound—stealthy. Holding his breath, he waited for it to be repeated. He heard it again, the mere ghost of a sound—the whisper of a sound, but significant as most whispers are.

He wiped his brow with his sleeve and told himself firmly that it was nerves, and nothing but nerves; but, against his will, he still listened. He fancied now that the sound came from his wife’s room, the other side of the landing. It increased in loudness and became more insistent, but with his eyes fixed on the door of his room he still kept himself in hand, and tried to listen instead to the wind and the rain.

For a time he heard nothing but that. Then there came a scraping, scurrying noise from his wife’s room, and a sudden, terrific crash.

With a loud scream his nerve broke, and springing from the bed he sped downstairs and, flinging open the front-door, dashed into the night. The door, caught by the wind, slammed behind him.

With his hand holding the garden-gate open, ready for further flight, he stood sobbing for breath. His bare feet were bruised and the rain was very cold, but he took no heed. Then he ran a little way along the road and stood for some time, hoping and listening.

He came back slowly. The wind was bitter and he was soaked to the skin. The garden was black and forbidding, and unspeakable horror might be lurking in the bushes. He went up the road again, trembling with cold. Then, in desperation, he passed through the terrors of the garden to the house, only to find the door closed. The porch gave a little protection from the icy rain, but none from the wind, and, shaking in every limb, he leaned in abject misery against the door. He pulled himself together after a time and stumbled round to the backdoor. Locked! And all the lower windows were shuttered. He made his way back to the porch, and, crouching there in hopeless misery, waited for the woman to return.

– IV –

He had a dim memory, when he awoke, of somebody questioning him, and then of being half pushed, half carried upstairs to bed. There was something wrong with his head and his chest and he was trembling violently, and very cold. Somebody was speaking.

“You must have taken leave of your senses,” said the voice of Hannah. “I thought you were dead.”

He forced his eyes to open. “Doctor,” he muttered, “doctor.”

“Out on a bad case,” said Hannah. “I waited till I was tired of waiting, and then came along. Good thing for you I did. He’ll be round first thing this morning. He ought to be here now.”

She bustled about, tidying up the room, his leaden eyes following her as she collected the beef-tea and other things on a tray and carried them out.

“Nice thing I did yesterday,” she remarked, as she came back. “Left the missus’s bedroom window open. When I opened the door this morning I found that beautiful Chippidale glass of hers had blown off the table and smashed to pieces. Did you hear it?”

Goddard made no reply. In a confused fashion he was trying to think. Accident or not, the fall of the glass had served its purpose. Were there such things as accidents? Or was Life a puzzle—a puzzle into which every piece was made to fit? Fear and the wind… no: conscience and the wind… had saved the woman. He must get the powder back from her drawer … before she discovered it and denounced him. The medicine … he must remember not to take it…

He was very ill, seriously ill. He must have taken a chill owing to that panic flight into the garden. Why didn’t the doctor come? He had come … at last… he was doing something to his chest… it was cold.

Again … the doctor… there was something he wanted to tell him … Hannah and a powder … what was it?

Later on he remembered, together with other things that he had hoped to forget. He lay watching an endless procession of memories, broken at times by a glance at the doctor, the nurse, and Hannah, who were all standing near the bed regarding him. They had been there a long time, and they were all very quiet. The last time he looked at Hannah was the first time for months that he had looked at her without loathing and hatred. Then he knew that he was dying.

8

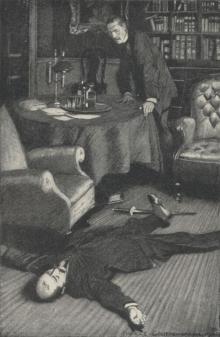

In the Library

The fire had burnt low in the library, for the night was wet and warm. It was now little more than a grey shell, and looked desolate. Trayton Burleigh, still hot, rose from his armchair, and taming out one of the gas-jets, took a cigar from a box on a side-table and resumed his seat again.

The apartment, which was on the third floor at the back of the house, was a combination of library, study, and smoke-room, and was the daily despair of the old housekeeper who, with the assistance of one servant, managed the house. It was a bachelor establishment, and had been left to Trayton Burleigh and James Fletcher by a distant connection of both men some ten years before.

Trayton Burleigh sat back in his chair watching the smoke of his cigar through half-closed eyes. Occasionally he opened them a little wider and glanced round the comfortable, well-furnished room, or stared with a cold gleam of hatred at Fletcher as he sat sucking stolidly at his brier pipe. It was a comfortable room and a valuable house, half of which belonged to Trayton Burleigh; and yet he was to leave it in the morning and become a rogue and a wanderer over the face of the earth. James Fletcher had said so. James Fletcher, with the pipe still between his teeth and speaking from one corner of his mouth only, had pronounced his sentence.

“It hasn’t occurred to you, I suppose,” said Burleigh, speaking suddenly, “that I might refuse your terms.”

“No,” said Fletcher, simply.

Burleigh took a great mouthful of smoke and let it roll slowly out.

“I am to go out and leave you in possession?” he continued. “You will stay here sole proprietor of the house; you will stay at the office sole owner and representative of the firm? You are a good hand at a deal, James Fletcher.”

“I am an honest man,” said Fletcher, “and to raise sufficient money to make your defalcations good will not by any means leave me the gainer, as you very well know.”

“There is no necessity to borrow,” began Burleigh, eagerly. “We can pay the interest easily, and in course of time make the principal good without a soul being the wiser.”

“That you suggested before,” said Fletcher, “and my answer is the same. I will be no man’s confederate in dishonesty; I will raise every penny at all cost

s, and save the name of the firm—and yours with it—but I will never have you darken the office again, or sit in this house after to-night.”

“You won’t,” cried Burleigh, starting up in a frenzy of rage.

“I won’t,” said Fletcher. “You can choose the alternative: disgrace and penal servitude. Don’t stand over me; you won’t frighten me, I can assure you. Sit down.”

“You have arranged so many things in your kindness,” said Burleigh, slowly, resuming his seat again, “have you arranged how I am to live?”

“You have two strong hands, and health,” replied Fletcher. “I will give you the two hundred pounds I mentioned, and after that you must look out for yourself. You can take it now.”

He took a leather case from his breast pocket, and drew out a roll of notes. Burleigh, watching him calmly, stretched out his hand and took them from the table. Then he gave way to a sudden access of rage, and crumpling them in his hand, threw them into a corner of the room. Fletcher smoked on.

“Mrs Marl is out?” said Burleigh, suddenly.

Fletcher nodded.

“She will be away the night,” he said, slowly; “and Jane too; they have gone together somewhere, but they will be back at half-past eight in the morning.”

“You are going to let me have one more breakfast in the old place, then,” said Burleigh. “Half-past eight, half-past—”

He rose from his chair again. This time Fletcher took his pipe from his mouth and watched him closely. Burleigh stooped, and picking up the notes, placed them in his pocket.

“If I am to be turned adrift, it shall not be to leave you here,” he said, in a thick voice.

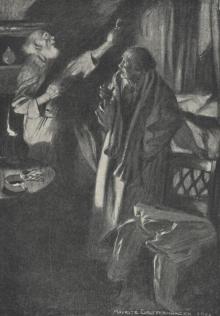

He crossed over and shut the door; as he turned back Fletcher rose from his chair and stood confronting him. Burleigh put his hand to the wall, and drawing a small Japanese sword from its sheath of carved ivory, stepped slowly toward him.

_preview.jpg) Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection)

Sailor's Knots (Entire Collection) The Monkey's Paw

The Monkey's Paw Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II

Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II Odd Craft, Complete

Odd Craft, Complete The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection

The Lady of the Barge and Others, Entire Collection Deep Waters, the Entire Collection

Deep Waters, the Entire Collection Three at Table

Three at Table Light Freights

Light Freights Night Watches

Night Watches The Three Sisters

The Three Sisters Ship's Company, the Entire Collection

Ship's Company, the Entire Collection His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts

His Lordship's Leopard: A Truthful Narration of Some Impossible Facts Fine Feathers

Fine Feathers My Man Sandy

My Man Sandy Self-Help

Self-Help Captains All and Others

Captains All and Others Back to Back

Back to Back More Cargoes

More Cargoes Believe You Me!

Believe You Me! Keeping Up Appearances

Keeping Up Appearances The Statesmen Snowbound

The Statesmen Snowbound An Adulteration Act

An Adulteration Act The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches

The Old Soldier's Story: Poems and Prose Sketches Husbandry

Husbandry Love and the Ironmonger

Love and the Ironmonger The Old Man's Bag

The Old Man's Bag Dirty Work

Dirty Work Easy Money

Easy Money The Lady of the Barge

The Lady of the Barge Bedridden and the Winter Offensive

Bedridden and the Winter Offensive Odd Charges

Odd Charges Friends in Need

Friends in Need Watch-Dogs

Watch-Dogs Cupboard Love

Cupboard Love Captains All

Captains All A Spirit of Avarice

A Spirit of Avarice The Nest Egg

The Nest Egg The Guardian Angel

The Guardian Angel The Convert

The Convert Captain Rogers

Captain Rogers Breaking a Spell

Breaking a Spell Striking Hard

Striking Hard The Bequest

The Bequest Shareholders

Shareholders The Weaker Vessel

The Weaker Vessel John Henry Smith

John Henry Smith Four Pigeons

Four Pigeons Made to Measure

Made to Measure For Better or Worse

For Better or Worse Fairy Gold

Fairy Gold Family Cares

Family Cares Good Intentions

Good Intentions Prize Money

Prize Money The Temptation of Samuel Burge

The Temptation of Samuel Burge The Madness of Mr. Lister

The Madness of Mr. Lister The Constable's Move

The Constable's Move Paying Off

Paying Off Double Dealing

Double Dealing A Mixed Proposal

A Mixed Proposal Bill's Paper Chase

Bill's Paper Chase The Changing Numbers

The Changing Numbers Over the Side

Over the Side Lawyer Quince

Lawyer Quince The White Cat

The White Cat Admiral Peters

Admiral Peters The Third String

The Third String The Vigil

The Vigil Bill's Lapse

Bill's Lapse His Other Self

His Other Self Matrimonial Openings

Matrimonial Openings The Substitute

The Substitute Deserted

Deserted Dual Control

Dual Control Homeward Bound

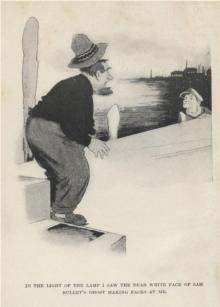

Homeward Bound Sam's Ghost

Sam's Ghost The Unknown

The Unknown Stepping Backwards

Stepping Backwards Sentence Deferred

Sentence Deferred The Persecution of Bob Pretty

The Persecution of Bob Pretty Skilled Assistance

Skilled Assistance A Golden Venture

A Golden Venture Establishing Relations

Establishing Relations A Tiger's Skin

A Tiger's Skin Bob's Redemption

Bob's Redemption Manners Makyth Man

Manners Makyth Man The Head of the Family

The Head of the Family The Understudy

The Understudy Odd Man Out

Odd Man Out Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary

Once Aboard the Lugger-- The History of George and his Mary Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence Blundell's Improvement

Blundell's Improvement The Toll-House

The Toll-House Dixon's Return

Dixon's Return Keeping Watch

Keeping Watch The Boatswain's Mate

The Boatswain's Mate The Castaway

The Castaway In the Library

In the Library The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre

The Monkey's Paw and Other Tales Of Mystery and the Macabre